by Prof. Alison Smith (University of Toronto)

As I spent time reading files and writing about Ivanovo, one of the things I wondered about is how exactly the spate of manumissions that first created this odd part-serf/part-industrial society happened. My full investigation into this has now been published in Past & Present (#244) as “A Microhistory of the Global Empire of Cotton: Ivanovo, The ‘Russian Manchester’”. Obviously it happened when a group of serfs gained their manumission, but that’s not actually a simple thing. Manumission was not in general an unknown part of serf life, and a number of accounts of Ivanovo note that the Ivanovo serf E. I. Grachev had received his freedom back in 1802. But that had been a single instance of manumission, and since then Ivanovo had been developing into a major textile center without additional cases over the next two decades. Then, suddenly, in the middle of the 1820s, something changed, as a dozen or so serfs gained their freedom over the course of just a couple of years. The short time period in which this number of serfs gained their freedom is still a clear sign of some specific event.

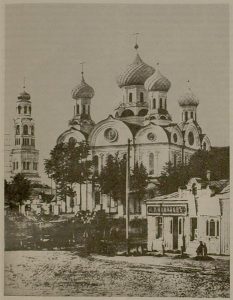

The Church of Christ’s Birth in Ivanovo, Source: Фотосайт Владимира Побединского.

Part of the answer to this question almost certainly has to do with something that has nothing to do with Ivanovo itself: Sheremetev’s age. Born in 1803, and orphaned just a couple of years later, he only gained control of his estates from his guardians in the middle of the 1820s. Before then, he had just barely begun to think of manumitting serfs. In 1819, his former wetnurse, Anna Danilova, and her family, were granted freedom through Sheremetev’s personal desire. This was an isolated incident, though, and because at that point he was still a minor, Emperor Alexander himself had to approve the manumission.

The real shift seems to have happened in 1824, when the household serf A. V. Nikitenko convinced Sheremetev to free him. According to Nikitenko’s memoirs, in the early 1820s Sheremetev was under the influence of friends and family members who opposed the very idea of manumission. Nikitenko, however, was no ordinary serf, but rather one who had gained a good education and come to the attention of a number of important friends who began to speak on his behalf. As a result, Sheremetev finally agreed to see him at his St. Petersburg mansion on October 11, 1824. “What am I to do with this fellow?” Nikitenko reports Sheremetev as saying at the meeting. “At every step I meet his supporters. Prince Golitsyn, Countess Chernysheva, my fellow officers, everyone demands that I give him freedom. I’ve been forced to agree, although I know that [my relatives] won’t like it.” And, indeed, Sheremetev did agree, and granted Nikitenko his freedom.

In Nikitenko’s memoirs, this moment is the climax, the end of a story of his manumission. But it was also a beginning, and not only for Nikitenko’s new life as a free man. This also seems to have been the moment when Sheremetev decided that manumission was an acceptable act, and that he was in principle, at least, open to petitions from serfs asking for their freedom.

Continuing my musings about motivations, I think there are two ways of interpreting this new openness. One is as a new moral interpretation of serfdom. There was certainly a hardline vision of autocratic Russia in which nobles were nobles and serfs were serfs and never should that change. Sheremetev’s son Sergei later described his father as a man of “weak character” but with a strong belief in tsarist authority, and he had family members arguing for this hard interpretation of serfdom. Freeing Nikitenko was a first step in envisioning serfs as possible independent people, and so indicated a new moral, or ethical outlook that allowed for manumission.

But just as possible is a second interpretation—that Sheremetev was moved by purely economic motivations. He got money out of manumissions. Not Nikitenko’s manumission, but all the rest. Later on that was certainly the case—in 1855 Sheremetev’s estate administration sent out a notice to all his estates telling “anyone who wants to receive manumission” to make an offer. I haven’t come across anything like that from earlier, but that may have been the mechanism that caused the several surges in manumissions at earlier dates, as well.

In any event, news of this new willingness to manumit got out—perhaps through a formal notice, perhaps through other Sheremetev serfs traveling to the St. Petersburg office, and then on to Moscow or to villages and estates further afield. Some of the great serf traders of Ivanovo already had extensive networks in the capitals, and corresponded regularly. Later records suggest that these and other networks could transmit news quite quickly. Andrei Fedorov Zavertkin, an Ivanovo serf, was freed as of February 1830. Only two months later, in April, his “cousin by family name” Ivan Ivanov Zavertkin, an Ivanovo serf who had been living for decades in Perm, working at one of the Demidov factories there, wrote to Sheremetev asking for his freedom, and citing his cousin’s manumission as the impetus for his own request.

And news did spread quickly. Nikitenko reported a specific date, October 1824. The first Ivanovo serf freed, Savva Shomov, got his freedom in 1826, although he was not resident in the village. The first of the Ivanovo manufacturers to buy their freedom were the Garelin brothers, in 1827, and their manumission became the model for the other agreements signed over the next several years. These single moments, whether Nikitenko’s conversation, Shomov’s request, or the Garelin brothers’ agreement, were important in and of themselves, and also as models or precedents for all the later actions that made Ivanovo what it was.

This blog post originally appeared as “Ivanovo: Manumission” on the Russian History Blog on 30/06/2016. It is reblogged here with Prof. Alison Smith’s kind permission.

Alison also wrote a wider series of blog posts for the Russian History Blog about the experience of conducting the research that became “A Microhistory of the Global Empire of Cotton: Ivanovo, The ‘Russian Manchester’” which appears in Past & Present #244. They can be read here.

Sources: I wrote quite a bit about manumission in “Freed Serfs without Free People: Manumission in Imperial Russia,” AHR 118, no. 4 (October 2013): 1029-51; also: A. V. Nikitenko, Moia povest’ o samom sebe (St. Petersburg, 1900), 203-11 (translated as Up from Serfdom: My Childhood and Youth in Russia, 1804-1824, by Helen Saltz Jacobson (New Haven, 2001)); S. D. Sheremetev, Memuary graft S. D. Sheremeteva, vol. 2 (Moscow, 2005), 359; Iakov Garelin, “Selo Ivanovo, v istoricheskom i statisticheskom otnosheniiakh,” Trudy Vladimirskogo gubernskogo statisticheskogo komiteta 5 (1866): 19-20 (Grachev’s manumission). Archival files include RGIA f. 1088, op. 3, d. 956 (Ivan Ivanov Zavertkin’s request); d. 1051 (the 1855 offer to manumit serfs); d. 1624 (Danilova’s manumission); RGADA f. 1287, op. 5, dd. 3503, 5389 (files of serf business correspondence), d. 5636 (the Garelin brothers’ manumission); op. 6, d. 301 (Savva Shomov’s manumission), d. 335 (Andrei Fedorov Zavertkin’s manumission).