news and updates on the Past & Present Blog

BLOG

The "Immobility" Past & Present Virtual Issue

By Josh Allen - June 28, 2025 (0 comments)

by the Past & Present editorial team

Three of the 2023-25 Past and Present postdoctoral fellows Drs. Lamin Manneh, Ana Struillou and Malika Zehni (Institute of Historical Research, London) have edited a virtual issue of the journal on the subject of Immobility.

In their introduction they explain that:

“Increasingly, since the early years of the twenty-first century, some have questioned the relevance of historians’ ‘fetishization of mobility’ in an era of closing borders. This has led to greater attention being placed on systems of ‘regulation and intervention’ that shape global migration. Shifting away from the narratives centred on movement and fluidity, we argue that immobility is not a mere lack of movement: it is about the power relations and barriers that enforce, experience, and resist stillness. By delving into the archives of Past and Present, we aim to construct a conversation around the processes of enforcing, experiencing, and challenging immobility. We have found that immobility shapes the experiences of both the historical actors found in the journal and the historians and scholars who write these histories.”

Outlining the basis of their interest in the topic and why this should be a matter of interest to historians working in the contemporary moment.

Thanks to our publisher Oxford University Press all non-Open Access articles in the virtual issue are currently free to read.

If you are interested in previous virtual issues of Past & Present the full archive is avaliable here.

Reflections upon "What have the English ever done for us? English Reformations in Early Modern Europe"

By Josh Allen - June 10, 2025 (0 comments)

by Kate Shore (Lincoln College, University of Oxford) and Dr. Fred Smith (Balliol College, University of Oxford)

What have the English ever done for us? This central question guided participants in a one-day workshop, organised by Fred Smith and Kate Shore, exploring the European impact and legacy of England’s early modern reformations. Once seen as insular and introverted, historians have increasingly come to recognise the extent to which England’s reformations, both Protestant and Catholic, developed in close and intimate dialogue with religious changes elsewhere throughout Europe. However, the history of Europe‘s many reformations and counter-reformations is still often told without much reference to England. Indeed, it is often assumed that England’s reformations had relatively little to offer their continental counterparts: as Diarmaid MacCulloch once suggested, ‘the flow of ideas in the [English] reformation seems at least at first sight to be a matter of imports from abroad, with an emphatically unfavourable balance of payments.’ The workshop, held in Balliol College, Oxford, on 27 March 2025, sought to interrogate this narrative by bringing together an international group of historians, literary scholars and theologians.

Over the course of 12 papers and lively discussion, a number of things became clear. The first was the extent to which England’s reformations were a topic of considerable interest throughout early modern Europe. Information about English events travelled quickly: Charlotte Methuen (University of Glasgow) emphasised how well-informed German Lutherans were about English affairs. Indeed, after Anne Boleyn was executed on 19 May 1536, Philipp Melanchthon was not only aware of the event but also passing on details in correspondence only ten days later. English reformations captured the imagination of their wider European peers and were integrated into the literary traditions of other countries. Tadhg Ó hAnnracháin (University College Dublin) brought to life the Italian tale of Il Cappuccino Scozzese by Giovanni Battista Rinuccini (1592-1653), which used a fictionalised life of George Leslie, a Scottish Capuchin monk, to unpick the tensions of religious conversion and familial relationships. Deborah Forteza (Covenant College, Georgia, USA) explored the different ways in which the tale of Henry VIII appeared in Spanish literature, from history writing to comedic plays. There was engagement with English reformations as far afield as Greece: Anatasia Stylianou (Humfrey Wanley Visiting Fellow at the Bodleian Library) detailed the exploits of Venetian Greek Nikandros Noukios (c. 1500-1556) who came to England and wrote a Greek account of the early English reformation.

Many of the papers also underlined the dense networks of connections linking England with Europe. James Kelly (University of Durham) spoke about those English Catholics who joined religious orders on the continent, whilst Morten Fink-Jensen (The Saxo Institute, Copenhagen) drew out the Anglo-Danish connection: Miles Coverdale received a very warm welcome in Denmark in 1555 and, in the seventeenth century, the University of Oxford was the place to study for future Danish theologians and politicians.

English reformations, then, were far from unknown on the continent. However, many papers went further by considering the extent to which such communications networks and perceptions helped inform religious change in Europe. A recurring theme tackled by many of the papers was just how difficult it is to pin down ‘influence’ – a problem confronted head on by Dorothea Wendebourg (Humboldt Universität, Berlin) in her paper exploring the influence of the English Reformation in the Holy Roman Empire. As Wendebourg explained, the role of German reformers in shaping the contours of English reformations is well-known and extensive. However, all relationships, no matter how imbalanced, are at least to some extent reciprocal – we just have to approach the question of ‘influence’ more omnivorously. In particular, Wendebourg underlined the importance of looking beyond a traditional focus on theological influence (English reformations were, undeniably, somewhat derivative of European ideas in this sphere) to consider instead the European significance of England’s reformations in more liturgical, ecclesiological and administrative senses. Once we do this, she argued, we can begin to see German reformers engaging more creatively and constructively with English ideas. This was an idea taken up by Kate Shore (Lincoln College, Oxford) in her paper, which explored the printing and circulation of German and Latin translations of Thomas Cranmer‘s writings, especially the Edwardian Order of Communion (1548). Meanwhile, Fred Smith (Balliol College, Oxford) underlined the significance of Mary I’s programme of Protestant persecution for informing French approaches to heresy in the 1550s: the French Cardinal, Charles de Guise, consciously appropriated aspects of the Marian inquisitorial campaign‘s structural organisation for use in France. Several of the participants also stressed that the influence of the English Reformation on Europe was not limited to the sixteenth century: Fink-Jensen, Wendebourg and Shore, for example, all stressed the importance of English Puritan writings for German and Danish proto-pietism in the seventeenth century and beyond.

However, perhaps the theme that came through most strongly across many of the papers was the profound European influence of English reformations in a more rhetorical sense – the power of ‘The English Reformation‘ as a narrative to conjure with. Wendebourg, for example, underlined the importance of that narrative for German reformers for whom the success of Protestantism outside Germany proved the catholicity and thus legitimacy of their reformation. The rhetorical force of the English Reformation was perhaps at its most potent in relation to martyrdom. Mirosława Hanusiewicz-Lavallee (John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Poland) discussed the reception of English martyrs in Poland-Lithuania. Lacking their own martyrological tradition, Polish translators repurposed English martyrological narratives, particularly those of John Foxe and Edmund Campion. Anne Dillon (Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge) echoed Hanusiewicz-Lavallee’s thoughts for the Spanish context: lacking their own continuity of martyr witness, Spanish charterhouses decorated their interiors with paintings of English martyrs. Meanwhile, James Kelly emphasised that English monasteries and convents in continental Europe became a powerful representation of the persecuted church on one’s doorstep. This gave such communities a powerful religio-cultural caché which helped them become standard bearers of Catholic reform. Katy Gibbons (University of Portsmouth) reflected on the ways in which European narratives also shaped the identity of English martyrs: Thomas Percy’s political involvement in the Northern Rebellion of 1569 made him an uncomfortable figure of veneration for English Catholics, but, in the rest of Europe, he could be sanitised and added to the tales of English Protestant persecution. Gibbons also emphasised the importance of the networks of religious orders in amplifying the stories of English martyrs. Details could be lost in translation, but the narratives of the English Reformation, with its tales of life and death, became a powerful tool and shorthand in the literature, religious writings and art of early modern Europe.

Ultimately, what the workshop really highlighted is that, despite its location on the geographical periphery, England was an important part of European conversations about religious change. By changing our frame of reference and looking at the English Reformation through European eyes, we can not only gain a new understanding of the English Reformation itself – its significance, idiosyncrasies and legacy– but also encourage historians to think more carefully about the ways in which religious ideas propagate, interact and merge.

Unpacking Jewish Dis/Connections: A Mediterranean Journey of Memory, Identity, and Mobility

By Josh Allen - May 12, 2025 (0 comments)

by Dr. Sasha Goldstein-Sabbah (University of Groningen)

From April 6-8 2025, the historic halls of the University of Warsaw became the vibrant meeting ground for sixteen scholars from across Europe converging to rethink and reframe Jewish histories through a Mediterranean lens. The workshop, titled Jewish Dis/Connections across and beyond the Modern Mediterranean, offered more than a gathering of minds—it was an invitation to rethink boundaries, identities, and narratives that have long defined Jewish studies in Europe.

Why the Mediterranean, Why Now?

Traditionally, European Jewish history has centered on communities in Central, Western, and Eastern Europe. Southern Europe and the Mediterranean have often been either marginalized or treated as outliers in scholarly discourse. This workshop sought to flip that script.

Guided by the organizing team—Dr. Magdalena Kozłowska (University of Warsaw), Dr. Noëmie Duhaut (University of Southampton), and Dr. Sasha Goldstein-Sabbah (University of Groningen)—the event proposed an integrative approach to Jewish history. It focused on mobility, not just of people, but of ideas, objects, languages, and institutions. As modern historians turn increasingly toward transnational and transimperial perspectives, this gathering highlighted how Jewish lives in and around the Mediterranean challenge established categories and regional divides.

A Crossroads of Scholarship

Over three days, participants dove into a panoply of themes: from nationalism and empire to gender, race, and commemoration. The unifying thread? The complex, often contradictory nature of Jewish mobility and identity in Mediterranean contexts.

In a thought provoking keynote, Prof. Matthias B. Lehmann (University of Cologne) explored what a Mediterranean framework might bring to modern Jewish history. Building on S.D. Goitein’s famed application of this approach to the medieval Geniza world, Lehmann encouraged scholars to view the Mediterranean not simply as a connector but also as a site of rupture and redefinition.

Matthias B. Lehmann giving the Keynote address in Warsaw April 2025, photograph by Noëmie Duhaut all rights reserved (2025)

What emerged was a rich portrait of the Mediterranean as a space where Jewish identity has been shaped and reshaped—through colonial entanglements, economic migrations, cultural affiliations, and diasporic memory.

From Algeria to the Negev: Snapshots of a Disconnected Yet Intertwined World

The range of presentations spoke to the diverse and dynamic range of research being conducted in Europe.

Eliaou Balouka’s work on Jewish-Muslim symbioses in Algeria unearthed little-known stories of shared mourning rituals and theological overlap—histories often eclipsed by modern polarizations. Dr. Roy Shukrun flipped the lens to post-independence Israel, where Moroccan Jewish migrants negotiated their North African pasts within the state-building landscape of the Negev.

Other presenters followed the threads of mobility through less obvious routes. Lida Dodou reimagined the Jewish migration from Salonika, traditionally viewed through its maritime port, by tracing rail connections to Hapsburg Europe. Dr. Dario Miccoli followed the Jews of Rhodes across the globe, showing how these movements were driven by both opportunity and trauma—from Fascist persecution to the Holocaust and decolonization.

Meanwhile, Dr. Noëmie Duhaut and Dr. Paris Papamichos-Chronakis spotlighted Jewish involvement in diplomacy and humanitarianism. Their work revealed Jews as not just passive recipients of aid or displaced peoples, but also as active players in shaping transnational relief efforts and legal networks.

These papers were not isolated inquiries—they spoke to each other, building a conversation that crisscrossed disciplines and geographies. From Calcutta to Beirut, from Libya to British India, participants traced how Jewish lives were constantly entangled in the shifting tides of empire, modernity, and memory.

Bridging Generations and Institutions

One of the workshop’s most central objectives was its commitment to inclusivity. PhD candidates and early career scholars shared the floor with established academics, generating a dynamic and collaborative atmosphere. For many, it was a rare chance to present in-progress work to a responsive, interdisciplinary audience.

By bringing this conversation into the heart of Europe, the organizers also made a statement: the study of Mediterranean Jewish history belongs within European academic institutions, not at their periphery. Warsaw—symbolically and geographically far from the Mediterranean—became an unlikely but fitting host, underscoring the workshop’s central message about interconnectedness and scholarly realignment.

Looking Ahead

The workshop was not just a one-off event. Plans are already in motion for a special issue in a peer-reviewed journal featuring selected papers, and future conference panels are in the works. Collaborations have been sparked with networks like “The Modern Mediterranean” and “EUME,” and a follow-up workshop is being discussed with Prof. Lehmann.

The workshop included two cultural excursions, to allow workshop attendees to appreciate the depth of Jewish history present in Warsaw. Participants toured the POLIN Museum and the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery, one thing was clear: this wasn’t just about history—it was about rewriting its map.

Grave monument in the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery, photograph by Noëmie Duhaut all rights reserved (2025)

A New Chapter in Jewish Studies

Jewish Dis/Connections across and beyond the Modern Mediterranean signaled a growing momentum within the field to challenge Eurocentric narratives and embrace more pluralistic, mobile histories. It invited scholars to consider the Mediterranean not just as a space of nostalgia or origin, but as a living framework—one that reframes Jewish experience through routes taken, borders crossed, and identities forged in motion.

As conversations sparked in Warsaw continue to ripple outward, this workshop has laid the groundwork for a reinvigorated, transregional approach to Jewish history—one that is as complex, dynamic, and interconnected as the Mediterranean world itself.

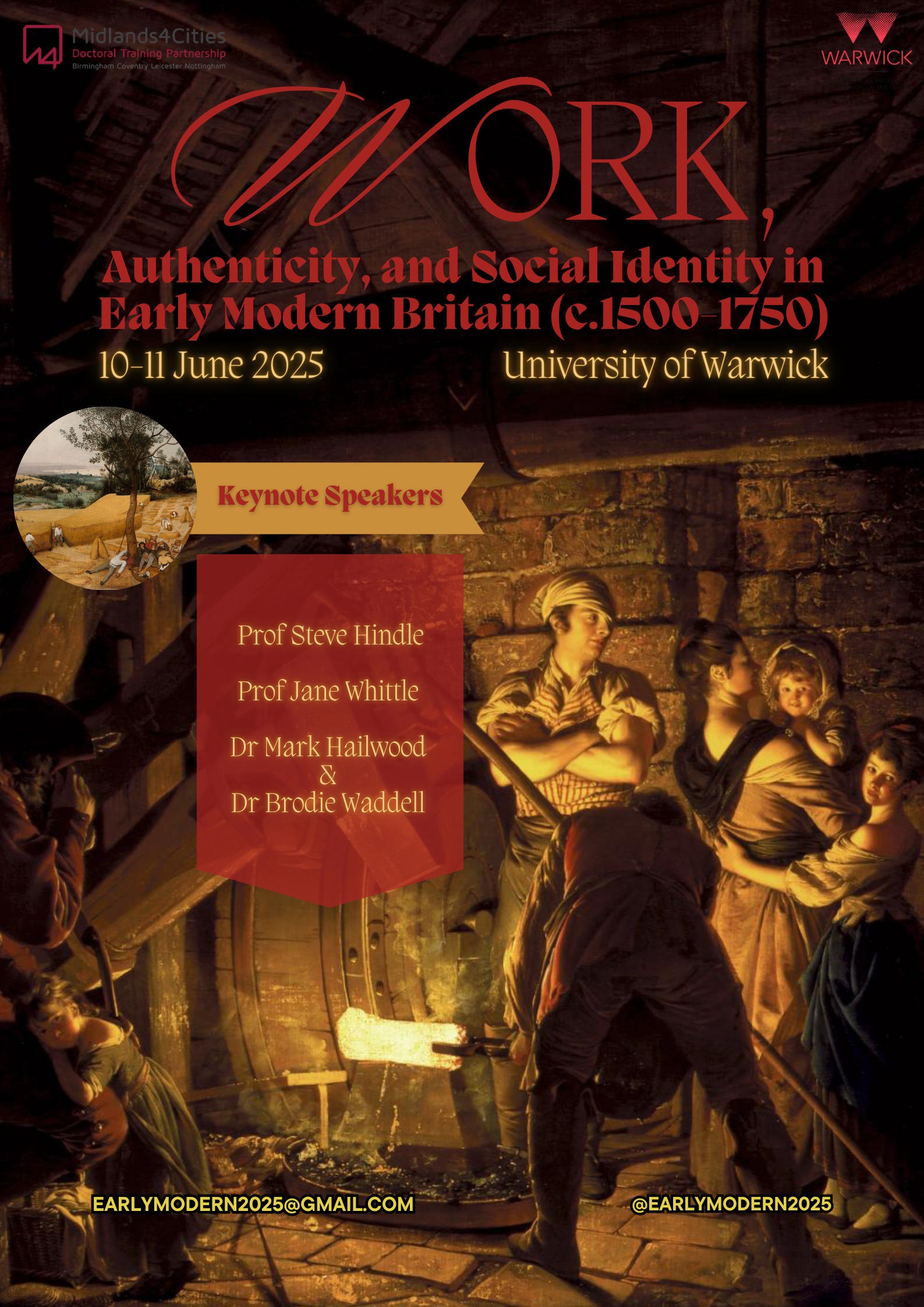

Programme and registration for Work, Authenticity and Social Identity in Early Modern Britain

By Josh Allen - May 8, 2025 (0 comments)

received from the event organisers

We are pleased to announce that the Work, Authenticity, and Social Identity in Early Modern Britain (c.1500-1750) Conference, supported by the Warwick Early Modern and Eighteenth Century Centre, the Doctoral Training Partnership AHRC-Midlands4Cities, the Society for the Study of Labour History, the Social History Society, and the Past & Present Society, will take place in the Scarman Conference Centre at the University of Warwick on 10-11 June 2025.

Keynote addresses will be delivered by Professor Steve Hindle (Washington University in St Louis), Professor Jane Whittle (University of Exeter), and jointly by Dr Mark Hailwood (University of Bristol) & Dr Brodie Waddell (Birkbeck, University of London).

Over the past several decades, scholars of British social and cultural history have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of early modern labour, social identity, and the self, demonstrating the analytical power of incorporating interdisciplinary approaches into their analyses alongside a diverse range of sources, from ballads to legal records. This conference seeks to develop this important body of work, inviting fresh perspectives on themes that have proven foundational to the study of early modern British social and cultural history. Non-elite early modern people spent a large portion of their lives ‘at work’, and their labouring experiences were often a central component of their identities and mental universes. We are interested in further unpacking these intersections between labour and identity, as well as the sociopolitical significance of how such relationships were communicated to individuals and communities—what we have capaciously termed ‘authenticity’ here, in hopes of prompting a variety of interpretations and responses.

Registration is essential! If you are interested in attending as a non-speaker, please contact Anna Pravdica at EarlyModern2025@gmail.com

Organised by Anna Pravdica (University of Warwick), Angus Crawford (University of Warwick), and Daniel Muddimer (University of Birmingham)

Programme

Day One, 10 June

8.00-9.25 Registration & Coffee

9.25-9.30 Welcome & Introduction

9.30-11.10 Panel 1 – Craftsmen, Trade, & Regulation

Bernard Capp (University of Warwick), Craft Identities: Collective Assertion and Personal Rejection

Owen Adams (University of Bristol), Defending the Myne: Maintaining Mining Autonomy and Livelihoods in the Forest of Dean from 1612

Anna Pravdica (University of Warwick), Representations of Labour: Economic Deceit and Social Subversion in Seventeenth-Century England

Ed Legon (Queen Mary, University of London), True or False: Authenticity and the Politics of Regulation in the Seventeenth-Century Textile Industry

11.10-12.30 Keynote Address

Steve Hindle (Washington University in St. Louis), The Tools and the Job: The Material Culture of Labour in Early Modern England

12.30-13.30 Lunch

13.30-15.10 Panel 2 – Religion & Nonconformity

Amy Stanning (Lancaster University), Catholic Participation in Civil Administration: The Surprising Case of the Land Tax in Lancashire

Daniel Muddimer (University of Birmingham), Catholic Royalist Activism and Authenticity

Evie Nash (University of Warwick), Shaping the Vagrant: Definitions of Vagrancy in Early Quaker ‘Sufferings’

Peter Lake (Vanderbilt University), Puritanism and Work

15.10-15.30 Coffee Break

15.30-17.10 Panel 3 – Music, Literature, & Performance

Noah Millstone (University of Birmingham), Reading as Labour in Early Modern Europe

Valentino Placanica (University of Bologna), ‘Because Musicians Have No Gold for Sounding’: Musicians, Migration, and Social Identity in Early Modern England, Between Craft and Performance

Yuqi Jiang (University of Birmingham), (Dis)crediting Old Wives’ Tales: Biblical and Classical Allusions in George Peele’s Play The Old Wives’ Tale (1595)

Angela McShane (University of Warwick), Women at Work in the Ballad Trade in Seventeenth-Century England

17.10-17.30 Coffee Break

17.30-18.50 Panel 4 – Gender, Domesticity, & Neighbourhood

Naomi Pullin (University of Warwick), Solitary Work and the Labour of Solitude

Abigail Carr (University of Leicester), Wet Nursing, Marital Status, and Familial Relationships in the Early Eighteenth Century

Alasdair McNeill (Birkbeck, University of London), Cheesemaking, Community, and Identity in Eighteenth-Century England

19.00-21.00 Conference Dinner

Day Two, 11 June

8.00-9.25 Breakfast & Coffee

9.25-9.30 Welcome & Introduction

9.30-10.50 Panel 5 – Poverty, Poor Relief, & Belonging

Ian Archer (University of Oxford), Pauper Apprenticeship in Early Modern London

Grace Marshall (Birkbeck, University of London), Disability and Physical Difference in Early Modern England

Naomi Tadmor (Lancaster University), Settlement and Identity, c.1662-1697

10.50-12.10 Keynote Address

Jane Whittle (University of Exeter), Housework as the Performance of Status in Early Modern England

12.10-13.10 Lunch

13.10-14.30 Panel 6 – Masculinity & Martial Identities

Joshua Racey (University College London), Social and Economic Effects of Garrisoning in the Reign of James II

Dylan Neill Andres (University of Bristol), Gender, Class, and Labour in the Popular Construction of the Martial Self

Melissa Glass (University of Calgary), Major George Strangeways versus John Fussell, Attorney at Law: The Emotional and Legal Labour of Conflicting Masculinities in Interregnum England

14.30-15.50 Panel 7 – Maritime Identities

Zara Money (University of Exeter), Billingsgate Fish Market: A Unique Centre of Maritime Cultural Identity

Amber Hogan (University of Bristol), Manuscript Mise-en-page and the Representation of Maritime Authority

Ryan Mewett (United States Naval Academy), Cut-rate Gentility: The Social Anxieties of Early Georgian Royal Navy Officers

15.50-16.20 Coffee Break

16.20-17.40 Panel 8 – Occupations & Labouring Identities

Nick Collins (University of Exeter), ‘The lab’ring Neat, (as you) may have their fill of meat’: The Construction of an Identity for Working Oxen in Early Modern England

Rebecca Giffard (University of Exeter), Tenant, Labourer, and Customer: The Multiple Identities Played by a Single Employee

Tim Reinke-Williams (University of Northampton), Public Houses and the Gendered Division of Labour in Seventeenth-Century England

17.40-19.00 Joint Keynote Address

Mark Hailwood (University of Bristol) & Brodie Waddell (Birkbeck, University of London), Work and Identity in Early Modern England: A Response to Hailwood and Waddell

Final Remarks & Goodbyes!

Past & Present is pleased to support this event and supports other events like it. Applications for event funding are welcomed from scholars working in the field of historical studies at all stages in their careers.

Programme and Registration for "How Sciences End"

By Josh Allen - May 1, 2025 (0 comments)

received from Dr. Michelle Pfeffer (Magdalen College, University of Oxford)

Dates: 11-12 July 2025

Location: Seminar Room, Radcliffe Humanities Building, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, Woodstock Road, Oxford OX2 6GG

Overview – Conference Theme and Goals

Historians have studied extensively how sciences begin—but how do they end? This is a crucial question for understanding how the labour of knowledge-making evolves. Previous attention to the founding, disciplining, and professionalisation of individual sciences has provided robust frameworks for thinking through the birth and growth of knowledge-making communities. Far less attention has been directed toward how those same communities decay, dissipate, or evolve beyond the contemporary boundaries of science. This conference seeks to cultivate case studies of the ends of sciences, and thereby to motivate a new approach to thinking about the developmental trajectories of scientific disciplines, communities, institutions, and the ordering of expert knowledge. A further aim is to strengthen the community of scholars with a shared interest in studying the ends of sciences.

A small lunch will be provided on both days of the conference. If you have any dietary requirements, please email Michelle at michelle.pfeffer@history.ox.ac.uk.

We hope to arrange a conference dinner for Friday 11 July following the keynote lecture. Once arrangements are finalised we will be in contact with all registered participants to ask if you’d like to attend.

Past & Present is pleased to support this event and supports other events like it. Applications for event funding are welcomed from scholars working in the field of historical studies at all stages in their careers.