by Dr. Benjamin Thomas White, University of Glasgow

This post originally appeared on the Refuge History blog and is reposted here with permission

Six years ago, popular demonstrations began against the Assad regime in Syria. Their brutal repression by the regime plunged the country into civil war, and since then Syria has become the world’s largest producer of refugees—almost five million at the latest count. But for most of its modern history, Syria didn’t produce refugees: it hosted them, in large numbers. There has barely been a decade in the last hundred and fifty years without a significant flow of refugees into what is now Syria, from the Balkan Muslim refugees of the late nineteenth century to the Iraqis who crowded into Damascus after the 2003 US invasion.

In a recently published article, I explore what this meant for the country in the 1920s and 30s: the period when the modern state of Syria emerged, nominally independent but dominated by France under a mandate from the League of Nations. In these years, the arrival and settlement of refugees helped to define modern Syria: its territory, its responsibilities as a state, and its national identity.

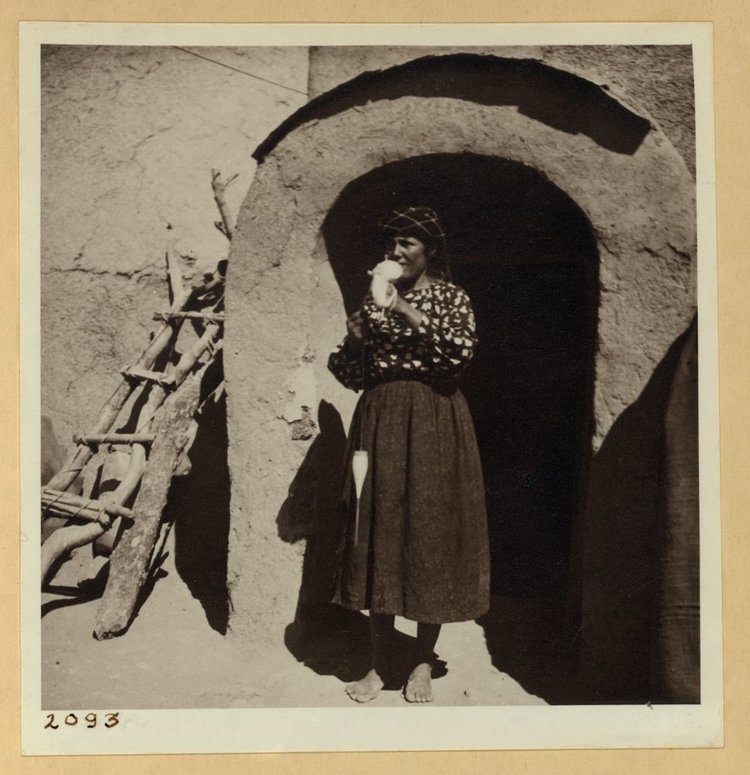

Assyrian refugees at Tell-Tamar and the Khabour River, July 21. Something of the twenty-seven villages built here by the League of Nations. The women still spin wool yarn and knit socks, etc. of it. LC-DIG-ppmsca-17416-00122 (digital file from original on page 65, no. 2093) https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.17416/?sp=122, Library of Congress

The area that became ‘Syria’ had been part of the Ottoman empire for four hundred years. After 1918, the division of Ottoman territory was contested between rival empires and nationalist movements. On maps, borders were agreed, disputed, and agreed again in diplomatic meetings. But it was the displacement of populations between the emerging states and mandates that drew those borders on the ground. As the priest, aviator, archaeologist, and French intelligence agent, Antoine Poidebard put it in 1928,

“The regroupment of the populations of Upper Mesopotamia (Upper Jazira and North Iraq) that is in course will necessarily be to the profit of the territory most quickly delimited and reorganized… [But] this settlement of Kurdish and Christian refugees requires the rapid solution of the delimitation of frontiers with Iraq and Turkey, the indispensable condition for the installation of a good administration closely controlled by the Mandatory Power”

In the post-Ottoman Arab provinces, the movement of refugees between different zones led national and mandatory authorities to establish firmer control across the territories that they claimed, and define their borders through topographical surveying, the building of border posts, and other means. State authorities needed to be present to monitor refugees, count their flocks, decide whether they were to be taxed, or disarm them and move them away from the border.

But it wasn’t just at the border that refugees helped define the national territory. Longer-term settlements helped establish the authority of the new state, with its capital in Damascus, right across Syria. In Aleppo, the mandatory state helped transform informal refugee camps created by Armenian genocide survivors into planned suburbs with modern amenities. In the countryside, it established agricultural colonies to settle refugees permanently—and, at the same time, develop Syria’s agricultural economy in ways that changed the relationship between state and territory.

The most extensive rural resettlement plan in interwar Syria was for Assyrian refugees from Iraq, several thousand of whom entered the country after 1933. An initial plan to settle them in western Syria’s Ghab plain failed. The Ghab was densely populated and farmed, so land was expensive, and settling refugees there was a political risk; the city of Hama, where Syrian Arab nationalism was strong, was also nearby. Deciding on a cheaper and politically safer option, the French built villages for the refugees by the Khabur river in the remote northeast—thereby making the region more firmly a part of Syria, through surveying and registration of land for tax purposes, agricultural development, and the provision of healthcare and policing for the refugees.

This helps explain why the arrival and settlement of refugees became politically explosive. The French ruled Syria, and decided to accept and settle refugees to benefit their own imperial interests: to create buffer zones with neighbouring states, for example, or to channel economic development in Syria to populations they trusted. The League of Nations participated in these plans. But under the terms of the League mandate, Syria was nominally independent, and the French were meant to be preparing it for self-government. Syrian Arab nationalists fiercely resented the infringement of Syria’s independence, and refugees became an important symbol of that—especially because while Syrians had no control over the arrival refugees, the French often paid for their resettlement with money from the Syrian state budget. The refugee settlements of the Khabur had better healthcare than most Syrian villages. In response, nationalists argued that they should govern Syria, and decide whether refugees should be allowed to enter.

In making these arguments, nationalists were circulating their own idea of the Syrian national territory. The newspaper al-Yawm warned in 1931 that ‘a thick line of towns and villages stretching along the northern Syrian borders’ had been transformed into an Armenian national home. By naming these remote places—‘Ayn Diwar, Dayrik, Damirqali, and over a dozen more—it claimed them as part of a Syrian national territory centred on Damascus. Similarly, by questioning refugees’ right to Syrian nationality (which Armenians had been granted under the new state’s 1924 nationality law, instituted by the French), nationalists were trying to propose their own definition of Syria’s national identity. Like almost everyone else in Syria, the refugees had been Ottomans until a few years earlier: if it wasn’t self-evident that they should be included in a definition of the Syrian nation, it wasn’t self-evident that they should be excluded either.

Assyrian refugees at Tell-Tamar and the Khabour River, July 21. Something of the twenty-seven villages built here by the League of Nations. Steel irrigating-wheel erected by the League of Nations. LC-DIG-ppmsca-17416-00125 (digital file from original on page 66, no. 2095) https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.17416/?sp=125, Library of Congress

By the time Syria became independent in 1946, its national territory was increasingly well defined, and there was no longer any threat that a part of it would become an ‘Armenian national home’. At that point, refugees could buttress national identity in a less exclusive way. The nationalist intellectual Muhammad Kurd Ali had once been hostile to Armenian refugees, but in his memoirs, published in the 1940s, he spoke warmly of them—and, particularly, of the ‘nobility of the soul and protection of the stranger’ that they had encountered in Syria. Armenians retained their Syrian nationality at independence, and the story of their welcome continued to form a self-flattering part of Syrian Arab nationalist stories about the nation.

This is not an exceptional history. Throughout Europe and the Middle East in the years after the First World War and the collapse of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires, new nation-states were defining themselves around and against refugees. The same happened around the world a few decades later as the colonial empires vanished.

Researching and writing the article as Syria descended into civil war, what struck me most about this history was its contemporary resonance with events in Europe as well as the Middle East.

As Syrian and other refugees have tried to enter Europe in the last few years, the borders around the EU and between its member states have been drawn more sharply. The question of who decides to let refugees into a country remains as controversial as ever, and parties like UKIP in the UK, the Front National in France, or Fidesz in Hungary, argue that only ‘taking back control’ of national borders from the EU can stem the flow. The provision of state services to refugees and asylum-seekers raises the same questions about states’ responsibilities to their own populations. In Britain, politicians hostile to refugees in the present continue to tell self-flattering stories about how we have welcomed refugees in the past. Nation-states still define themselves around and against refugees.

Many thanks to the excellent Refuge History network for allowing us to repost this blog