by Shahmima Akhtar (Birmingham), Carmen Gitre (Virginia Tech), Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez (Hawai’i, Mānoa)

The panel “Everyday Performance/Performing the Everyday: Exhibitions, Leisure, and Hospitality” assembled three papers that spoke to different types of performances and meaning-making, primarily from below, that operate within, against and alongside empire. All three papers addressed “spaces of encounter.” These spaces ranged from the public (coffee houses, street theatres, world’s fair exhibits, vaudeville stages) to the intimate (the home), but they engendered ephemeral, affective moments that constituted the everyday transactions and interactions of empire. Performances, repertoires, and rituals within such spaces both shored up and undermined imperial power. They hosted moments of consent, survival, resistance, and nostalgia. They were highly gendered and classed spaces, crucial sites for identity-formation for self, class, and nation. They were also fragile, fragmented, and contested. Within those spaces of encounter, people of all stripes forged new grammars and symbolic systems—oblique, humorous, deeply personal, or outright unsettling—that point to the creativity of resistance in particular.

The focus on the everydayness of these spaces and the way that they shaped the wider everydayness of empire allowed us to identify and explore encounters that could consolidate and/or unsettle empire, but which are frequently overlooked or treated as transparent in the existing historiography of empire.

Hawaiian lei venders, c. 1901 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Carmen’s focus on the nuances of working-class Egyptian identities that were cultivated in the coffeehouses and street theatres circa 1900 prompts us to think about how these spaces accommodated people very much interested in the question of the political subject and the most effective ways to access political power. In the raucous, smoky rooms frequented by men, the acts, scripts, stock characters, and improvisations of both performances and audience crafted a unique and critical sha’bi identity among property-less labourers new to urban areas.1 This identity mocked and negotiated effendi, or middle-class, prescriptions of Egyptian-ness and these performances, put on day after day in small theatres, were modes of social critique and nationalist fantasy.2

The feminized rituals of hospitality in Hawai‘i, meanwhile — as outlined by Vernadette —also afforded intimate, everyday spaces of encounter in which Native Hawaiians carved out dignity and defined their lives, even as colonial tourism sought to reframe indigenous hospitality as consent to empire. The erosion of indigenous productive time and creative practices, and of female social and political power, were thereby countered by the community rituals and domestic spaces that Hawaiians continued to nurture outside of capitalist time.

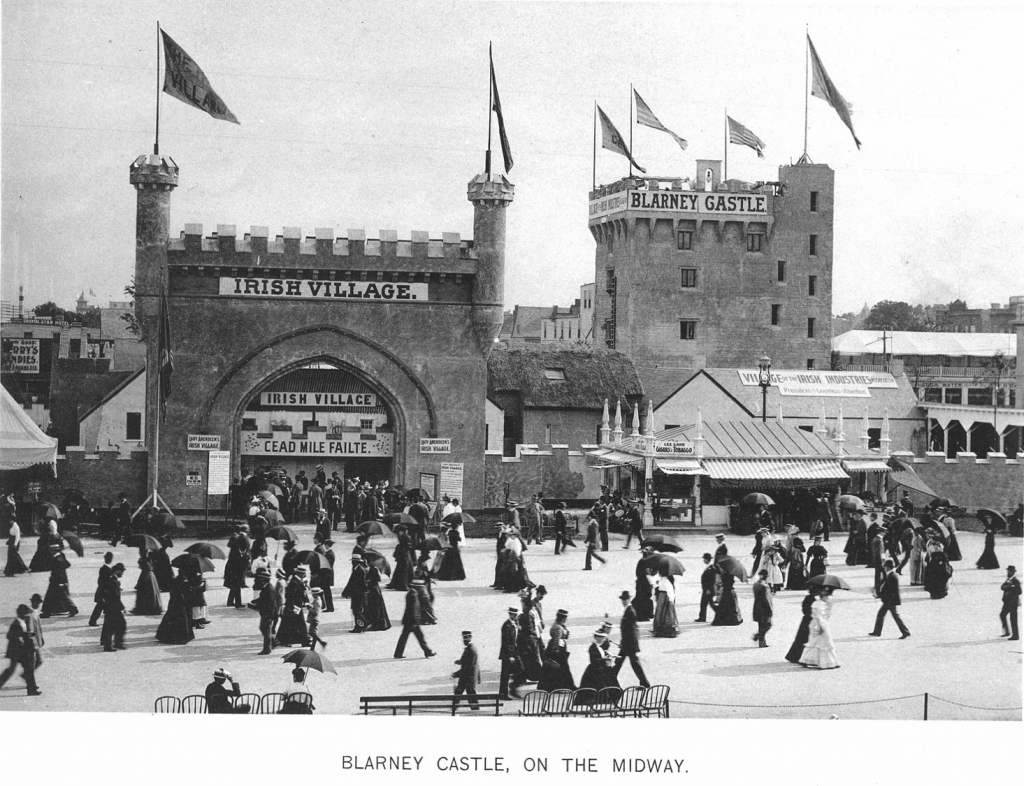

Finally, Shahmima’s close look at the Irish villages at the 1893 and 1897 World’s Fairs examined how these exhibits drew on the nostalgia of diasporic colonial subjects to animate differing visions of home, nation and independence. Regardless of the organizers’ intentions for the displays, Irish-American fair-goers themselves interacted with the exhibits in ways that exceeded the goals of the design, in the process transforming themselves from spectators into performers who actively made meaning about identity and nation.

“my photograph of the model café-chantant taken on June 27, 2010. The model is in the Egyptian National Folk Museum located in Cairo.”

All our papers attended to the importance of listening for and seeking alternative evidence of working-class agency, speech, acts and thoughts in these spaces of encounter. For instance, sha’bi theatre mocked a hegemonic effendiyya, forging a shared identity amongst working-class, factory labourers and preserving a place where local practices, creativity and fantasy were sustained. One can imagine the fluency of an audience in laughing at a joke, or understanding how a turn of phrase might transform a joke or song into a sharp political critique. Or how the Hawaiian term “aloha” in one instance is stripped of its meaning, and in another instance, is redolent of resistance and communal struggle. In Hawaii, commoditized lei-selling meant a modicum of labour sovereignty and avoidance of work on plantations. But engagement in the capitalist economy was never complete and exact. It was a performance, suspended when colonial tourist ships had sailed. Other kinds of performances, such as those undertaken by world’s fair attendees, breathed life into identities. In the Irish case, people walked away from the World’s Fair Irish villages literally carrying bits of the performance space as a promise to continue Irish values in a modern world. Walking through and collecting bits of “Sod maps” and turf cultivated nostalgia not to mourn but, rather, to draw strength from “touchstones of the past, and to promote a new, Irish-American future” thousands of miles away from the homeland. This occurred despite the policing of the fairground space to prevent such ‘stealing’ and indicates the blurring of behavioural norms and practices within the imagined country.

What our panel demonstrated so clearly, then, is that the concept of ‘everydayness’ can work in many exciting and unique ways. It touched on the materiality and performance of the symbols of identity and/ or resistance; the fragility and contested nature of spaces of encounter; and above all the nuanced and varied ways imperial frameworks play out in the everyday lives of ordinary people. This focus on working-class, often racialized and feminized subjects has pushed us to seek archives that are difficult to pin down, or to read existing colonial documents in more circuitous and oblique ways. The ephemera of performance, of tone, of affect, are hard to pin down, but yield important additions to the story of empire — particularly from perspectives that are more easily ignored.

Footnotes

1For more on the sha’b, see Joel Beinin and Zachary Lockman, Workers on the Nile: Nationalism, Communisim, Islam, and the Egyptian Working Class (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987); Ziad Fahmy Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011).

2For more on the effendiyya, see, Yoav Di-Capua, Gatekeepers of the Arab Past: Historians and History Writing in Twentieth-Century Egypt (Berkeley: University of Californa Press, 2009); Ilham Makdisi, Theater and Radical Politics in Beirut, Cairo, and Alexandria: 1860-1914 (Washington DC: Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, 2006); Lucie Ryzova, The Age of the Efendiyya: Passages to Modernity in National-Colonial Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).