by Dr. Brodie Waddell (Birkbeck, University of London)

In 1612, the Overseers of the Poor for Finchingfield in Essex spent just over £37 on payments to the parish’s poorest residents and related expenses. However, by the early 1650s they were spending over £100 every year and by the late 1690s average disbursements were over £200 annually. The payments kept rising in the decades to come, regularly exceeding £300 in the 1740s and hitting £543 in 1758.[1] Nearly half a century later, in response to a national survey into ‘the Expense and Maintenance of the Poor in England’, Finchingfield’s overseers reported that they spent £1,626 on ‘the whole Expenditure on Account of the Poor, in the Year ending Easter 1803’.[2]

The story told by these figures is, in some ways, simple and well-known. Under the so-called ‘Old Poor Law’ governed English welfare provision from 1598 to 1834, parishes across England raised money through local taxes to offer relief to ‘their’ poor. The amount they raised and distributed varied hugely across different regions and could also occasionally rise or fall suddenly from year to year, but over these two centuries parishes undoubtedly spent larger and larger sums. Finchingfield’s growing expenditures were only a small part of what Paul Slack called the ‘momentum’ of ‘the machine of social welfare’.[3]

Extract from overseers’ accounts for Great Gransden (Hunts), 1673-74. Huntingdonshire Archives, HP36/12/1, 45. Note the key line on the bottom right: ‘Our Disbursmentts are 05 16 04’.

Yet if we want to understand the effect of this ‘machine’ on the lives of the poor and the purses of the ratepayers, illuminating the speed and scale of this growth is important. All scholars of early modern welfare acknowledge the long-term rise in relief spending, but measuring it is another matter. The English government only attempted to estimate national relief expenditures on a handful of occasions before the nineteenth century and historians have only examined the spending of individual or small groups of parishes.

At Birkbeck, I regularly teach on the history of the poor relief system, but while preparing lecturers and leading seminars I regularly ran into questions that I could not answer. Could the expansion of funding devoted to poor relief keep up with population growth that meant there were more poor people in England almost every year? Could the amount of money received by the poor through this system cover the rising cost of living, especially in periods of sustained high food prices? Or, even more simply, was the scale of expansion seen in Finchingfield’s spending on poor relief typical or exceptional?

Almost a decade ago, in an attempt to answer these questions, I started gathering figures for relief spending from various manuscript overseers’ account books held at the county archives in my part of the country and extracted the key numbers from the few accounts from elsewhere that had been published in modern editions. Then in late 2013, I discovered that Jonathan Healey was similarly gathering data, conveniently from other regions of England.[4] Over the next few years, we continued pulling together material and incorporated figures very generously supplied by other historians who had undertaken projects focused on particular parishes. By 2019, we had data from 183 parishes and, after much trial and error, I found a way of collating this into a credible single ‘series’ stretching from 1600 to the end of the Old Poor Law in 1834. The results are now published in my article on “The Rise of the Parish Welfare State in England, c.1600–1800” published in Past & Present No. 253, November 2021.

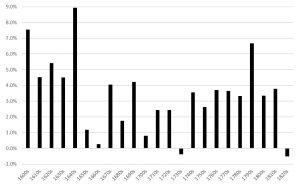

When we look at national spending over this long period, we see that the fastest rise in spending came in the early seventeenth and late eighteenth centuries, with some other moments such as the 1690s also standing out for their high growth rates. In between, there were many decades of more gradually rising spending and a couple where the amount barely increased at all. Yet, even in decades of slower growth, expenditures on the poor almost always grew faster than the rising population. What’s more, it also grew faster than economic expansion or price inflation, meaning relief continually expanded in ‘real’ terms even with more poor people and higher prices.

It would be easy to be see such findings as flattering the self-image of wealthier English people who saw themselves as both generous and efficient in their charity. However, rising spending was as likely to be driven by assertive ‘demand’ from below as generous ‘supply’ from above. The complaints and petitions of the poor, alongside the threat of crime and riot, helped to ensure that the annual disbursements recorded by overseers in Finchingfield and thousands of other parishes across the country rose almost every decade after the establishment of the poor relief system at the end of Elizabeth’s reign.

Footnotes

1Essex Record Office, D/P 14/8/1A, D/P 14/8/2.

2Abstract of Answers and Returns under the Act for Procuring Returns Relative to Expense and Maintenance of the Poor in England (Parliamentary Papers, 1803-4, no. 175), p. 156.

33 Paul Slack, Poverty and Policy in Tudor and Stuart England (1988), p. 182.

4He has examined our shared data from a different angle and will be publishing his analysis separately, but in the meantime his monograph demonstrates the value of a county-level investigation: Jonathan Healey, The First Century of Welfare: Poverty and Poor Relief in Lancashire, 1620-1730 (2014)