by Dr. Carol Symes, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Like many scholars who have turned their attention to medieval crusading movements in recent years, I am not a “crusade historian.” I’m trying to write a book on medieval texts as artifacts created by the mediation of multiple historical actors – many of them technically illiterate. My goal is to change the way we understand the evidentiary nature of texts, which we (modern, and even postmodern) historians tend to strip-mine for the meaning(s) of their written words. Everything we have learned about medieval documentary processes in the past few decades has revealed that these texts were shaped and conveyed by the specific circumstances of their negotiation and inscription; their fungible physical formats; and the embodied, performative contexts in which they were enacted, witnessed, displayed, declaimed, contested. Reading the writing is not enough. Pace Jacques Derrida, “il y’a toujours d’hors-texte.” Knowing what happened outside a medieval text is materially important because the conditions of its making and reception influenced what it said and how it worked – or didn’t.

It was strangely ironic, then, to find myself compelled to advance this argument by tackling the multiple near-contemporaneous histories of the First Crusade (1095-1099), none of which survives in anything close to a contemporary format. Instead, as I show in my recent Past & Present article: “Popular Literacies and the First Historians of the First Crusade”, accounting for these histories – many lost to us – means accounting for the fragile media through which they would have been transmitted: the perishable materials (parchment, maybe; but papyrus, cloth, wax, and wood as well), the chancy processes of manuscript transmission, the now-silent channels of oral communication and commemoration, the exigencies of memory and the exercise of power.

A medieval text on the edge of oblivion: leaf from a working set of by-laws created by a confraternity of jongleurs, now part of a manuscript codex in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (fr. 8541).

Thanks to exciting new scholarship, it is becoming clear that the apparent explosion of documentation in the eleventh and twelfth centuries C.E. was not new, and not necessarily the beginning of a shift “from memory to written record” in western Europe. Lay men and women in the lands of the former Roman Empire – and beyond – had been making, using, and keeping documents for centuries, often employing or expanding older models of record-keeping, but also introducing their own practical innovations, sometimes in their own vernaculars. But the scattered evidence of these widespread practices is only barely visible, thanks to the collaborative efforts of experts in many fields working in many different regions of what we are learning to call the medieval globe.

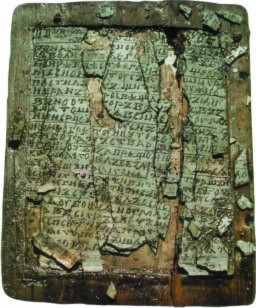

The Novgorod Codex: a palimpsest of wooden boards and wax pages, written (mostly) in Old Church Slavonic, probably during the 1010s. It was discovered during excavations of a twelfth-century boardwalk, in 2000.

Yet this evidence is paltry compared to the much larger percentage of written materials produced in clerical and monastic institutions, which had the advantage of housing many trained scribes and which were, thanks to their stability and longevity, uniquely situated to assemble and preserve texts – and to manipulate historical memory: if not that of their contemporaries, then that of modern historians. Increasingly, many of these institutions were able to establish local monopolies on the recording and archiving of transactions, which resulted in the gradual loss of documentary agency by lay individuals and communities, and often to their legal disenfranchisement.

So what I think we see happening, in the eleventh century, is either a resurgence of lay documentary activity in some places or the opening of new channels through which more people could access textual processes. But we also see a concomitant attempt, by clerical elites, to suppress that activity and safeguard the status quo. The capture of Jerusalem by a mongrel army of Franks, Normans, Rhinelanders, and others – with virtually no sustained papal support, spiritual or practical – was thus the catalyst for the creation and consumption of mediated texts. These men had opened a new chapter in sacred history and they (or their surviving friends and family members) wanted to write that history themselves, drawing on the narrative forms meaningful to them: song, epic, liturgy, anecdote. Indeed, some of those forms may have been augmented by other story-telling traditions and textual cultures encountered in the Mediterranean and Islamicate worlds, where the crusade’s home-bound monastic historians had never been.

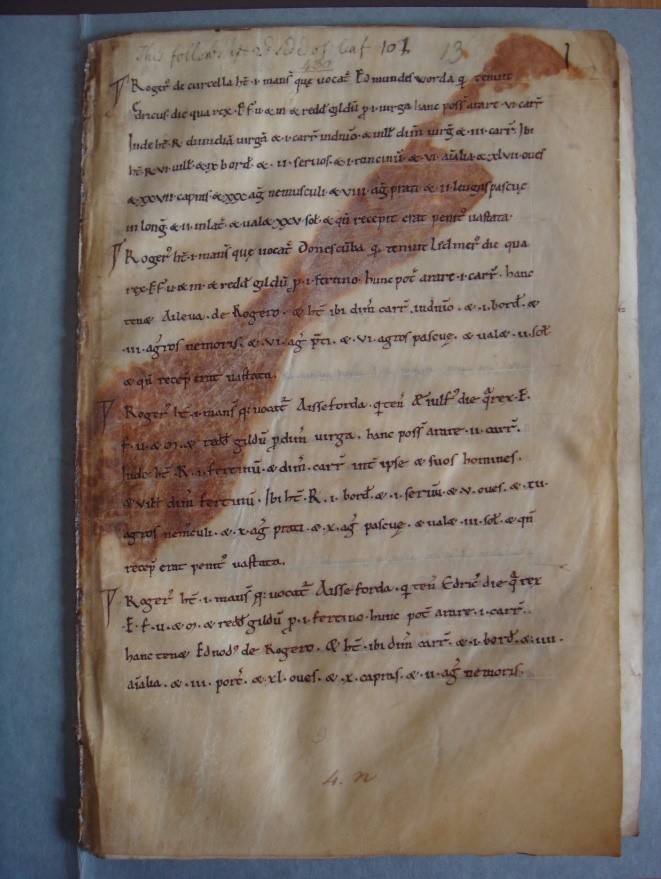

Medieval archives contained a wide variety of texts and other objects. The family archives of the twelfth century might well have juxtaposed little booklets of crusade narratives with weapons and relics brought home from the Holy Land. This particular booklet shows the indelible mark of the spearhead that was once left rusting on it. Closely contemporaneous with the First Crusade, it was copied c. 1086, during William the Conqueror’s survey of his realm. It should have been recycled (to stuff the bindings of books, to insulate a garment or hat) but it was remarkably preserved and is now housed among other such libelli in the library of Exeter Cathedral (MS 3500).

By reconstructing the documentary conditions of the era, then, we can begin to recognize how the first histories of this momentous expedition could have been created by lay or lowly clerical combatants – including the author(s) of the so-called Gesta Francorum – within a few years after the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099. Around 1107, however, these once multiple documentary perspectives were being actively suppressed by the Benedictine establishment of northern Francia. Horrified that unauthorized narratives were in wide circulation, these monastic authors (notably Guibert of Nogent, Baudri of Bourgeuil, and Robert of Reims) drew on their own sources (e.g. elite networks, Biblical exegesis) in order to craft more conventional histories that promoted their own agendas and that of the “reforming” Roman papacy. This papacy would reach the apogee of its power a century later, under the pontificate of Innocent III, who directed crusading fervor toward fellow Christians in Constantinople as well as toward new kinds of “infidels” within Europe.

At its core, this is a feminist argument – about the workings of medieval texts and about the historiography of the First Crusade. Although I mention women only once in my article (p. 60) and do not deal with issues of gender or race in any explicit way, my methodology is fundamentally attuned to exposing the power dynamics that have written certain people out of the historical record even when those people were fundamentally instrumental to the creation of the historical record. In fact, women were the real keepers and conveyors of historical memory in this era. The way they narrrated history, and what they chose to include and emphasize, would have been crucial to the framing and perpetuation of these first crusading texts. For example, modern crusade historians frequently express frustration about how little actual fighting gets recorded in extant early histories – that is, if one discounts the Old Testament battles recycled by armchair monastic historians. To me, this is another mark of these early histories’ proximity to that fighting and their authors’ need to help themselves and their audiences process the trauma of combat and loss.

A truly feminist methodology is inclusive. With that in mind, we need to ask what other assumptions and habits have prevented us(me) from reading medieval texts as fully as they deserve. What other actors and factors have we(I) left out of this story? For example, how has systemic racism shaped the norms and practices of medieval historiography in the modern world, and how has that contributed to the invisibility of certain people and phenomena? How has our discipline’s valorization of the single (male) author made it hard for us to grasp the plurality and gendered diversity of medieval authorship? How do older and newer forms of nationalism and xenophobia contribute to the ways we (mis)conceptualize medieval categories of difference, identity, religion, language, territory, etc.? How, indeed, have modern norms of textuality, and the fetishization of alphabetic literacy, prevented us from fully appreciating medieval texts and their makers?

A feminist historiography of warfare, or anything else, doesn’t merely consist in proving that women were involved in the crusades or examining the toxic politics of masculinity and misogyny in this era – although these are among the many necessary topics currently being addressed. It also has to mean a willingness to rethink what we think know about what happened, based on what we have learned about the delivery mechanisms of medieval texts and their frequently unnamed or occluded mediators. The silence that has engulfed these textual actors is deafening, and it was very often a silence deliberately imposed by those with a vested interest in amplifying their own voices: men who were in a better position to exercise documentary power via the destruction of some texts and the multiplication of others, at the expense of any outsiders, whether male or female, “heretic” or Muslim or Jew.

A feminist, gendered approach to textuality, meanwhile, pays critical attention to the fact that medieval texts were (and are) essentially embodied. Not only are they made of bodies (until the late thirteenth century, in northern and western Europe, parchment was the most prevalent and only durable writing material) they were prepared, at every stage, by bodies. Behind every surviving medieval manuscript are animals nurtured and slaughtered, the labors of farmers and shepherds and tanners, and maybe even the chronic malnutrition of peasant families who seldom had access to animal protein prior to the first global pandemic. For on the one hand, the Black Death’s terrifying rates of mortality eventually resulted in more sustainable modes of agricultural production and a healthier diet for survivors. On the other, this coincided with the more widespread availability of paper, which was cheaper and easier to use.

Moreover, medieval texts were experienced bodily. Of the vast majority that don’t survive, many would once have been put to the service of bodily needs: patching a shoe or lining a winter coat. The work of inscribing a medieval text was hard, physical labor. No legal document was valid unless it was publicly produced, read aloud, and physically ratified by witnesses, who were often called upon to touch it or to impress their personal seals on it. Books could be so heavy that they required a lectern, or small enough to fit in a palm. Texts were noisy, too: stiff parchment leaves crack loudly when they are turned, leather and wood bindings creak, iron fittings clank, pendant wax seals knock together like dried chestnuts. Such sensual details would have affected (and effected) the reception of a text. They ask us to reach out and grasp medieval texts in radical, old ways.