by Dr. Eoin Phillips (Ramon Llull University)

In July 1772, Captain James Cook took command of a state-sponsored voyage of exploration to circumnavigate the globe. Of the thousands of objects taken on board and brought back on that ship, few have received the attention of the timekeeper he came to refer to as his ‘trusty friend’, his ‘never failing guide’. The reason Cook took a timekeeper was because of the ambition of the British naval and natural philosophical establishment to establish a means of accurately finding longitude at sea. Finding the longitude of a ship at sea in the eighteenth century was regarded as a problem for several European states including the British. One result was that in 1714 in England, an Act of Parliament was passed to establish a Board of Longitude to facilitate attempts to devise a solution for finding longitude at sea through a series of public awards.

‘K1’, one of the timekeepers taken by Cook on his second voyage of exploration (1772 – 1775). Source: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/79143.html)

The dominant image of the relationship between those European voyages of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century and techno-scientific hardware has tended to make the claim that timekeepers for use at sea – those instruments that came to be called ‘chronometers’ – were, from the beginning, ‘trusty friends’ and ‘never failing guides’ for their users. This mirrors what I perceive to a broader understanding of the relationship between globalisation and precision technologies: that global movement depended upon having ingenious and reliable technologies. This in turn replicates a particular ambition and claim of the sciences: that their methods and experiments can work anywhere and at any time. It has been the task of many historians and sociologists of science since the 1980s to revise this claim; to show how the cultural and geographic contingencies through which scientific ideas and practices are formed always rely on more than the replication of codified procedures to make them work. The relationship between global claims and local practices are, they argue, mediated by people and instruments who have to be moved to make science work.

Pointy arrows: which way do they point?

There have been several models seeking to describe the relation between European techno-science and global homogenisation. Perhaps the most notorious is George Basalla’s three-stage model of the globalisation of ‘Western Science’ – where ‘science’ stood as a byword for truth, rationality, order, and civilisation. This model has received numerous critiques, most notably by Kapil Raj in Relocating Modern Science: here he demonstrates that many of the places where knowledge practices called science were done in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were actually not in western Europe. Meanwhile, Bruno Latour has offered a conceptually more appealing – yet arguably still problematic – version of the idea that global mobility relied upon the successful performance of European hardware, arguing that the supposed success of European long-distance voyages was rooted in the peculiar quality of certain instruments being both immutable and mobile.

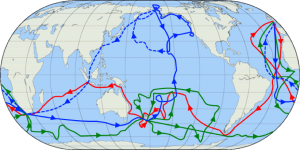

But perhaps the main driving force behind the ‘global’ approach to history has come from economic historians over the last thirty years. Describing an attempt to get away from histories of the nation state, a dominant idea of ‘the global’ has meant a particular kind of history of ‘connectedness’ or ‘integration’, which has typically focused on the movement of commodities. This approach has lent itself to maps such as this, where pointy arrows represent both the movement of commodities, and a resulting ‘integration’ or coming together of places around the world to form a global interaction. While I think this pointy-arrow approach to global history cannot be entirely dispensed with, I believe it shouldn’t serve as a guide to what ‘global’ histories, or accounts of globalisation, might look like.

Image: ‘Cook’s Voyages Map’ Source: The Mariner’s Museum and Park https://exploration.marinersmuseum.org/subject/james-cook/cooks-voyages-map/

One major problem with these accounts is their total flattening out of space, particularly ocean space, as water serves as a backdrop to emphasise how far commodities seem to have travelled. This implies that the movement of instruments, commodities and peoples is unproblematic; that these people and things are solid and inherently stable; and that cultural organisation in general and labour in particular act simply as lubricants for the successful flow of these commodities. These assumptions are especially problematic when we consider the manifold problems merchants continually faced in getting things to move uninterruptedly across water. This flattening out of space is indicative of what Philip Steinberg has called the representation of ‘non-territorialised’ oceans, which in the nineteenth century went hand-in-hand with industrial capitalism’s need to preserve freedom of mobility.1 The role of science and technology in ‘commodity-chain’ models of global history has largely been to provide explanatory reasons for the efficient, secure, and ordered movement of commodities across land and – mostly – sea.

Trusted Friends?

So, can we assume that high-tech European instruments like timekeepers were trusted to work?

On Cook’s second voyage, he had been assigned three timekeepers. These were sent out by the Board of Longitude along with strict instructions to keep each timekeeper in a special box and that ‘three good locks… be also provided and affixed to each box’. Keys were to be distributed amongst high-ranking officers – with Cook only receiving only one for each box – who were supposed to be co-present each time the timekeepers were wound or ‘computed’ against each other.2

Locks and keys had a very definite meaning in late eighteenth century England. As Peter Linebaugh notes in his brilliant The London Hanged, locks and keys were an essential part of the logic of capitalism that had begun with the extensive system of enclosure that was being accelerated in the eighteenth century. This moved from the private ownership of houses through to very personal items like bureaus and jewelry boxes – all secured by lock and key. The fact that the Board of Longitude had not simply entrusted the keys to Cook, as captain of the two vessels, speaks to the more generalized, and intense, web of mistrust that characterized European oceanic travel. This mistrust was only exacerbated when expensive instruments were involved.

Part of the reason for this mistrust is that until at least the 1830s, the accuracy of instruments such as timekeepers to calculate longitude was being tested alongside a whole range of astronomical and navigational equipment. Testing the instruments, therefore, required an attempt at imposing order on voyages from places such as the state-funded Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Timekeepers on voyages of discovery were routinely accompanied by a Greenwich-trained astronomer, who also deployed a range of other instruments and techniques for measuring and testing longitude. the more generalized, and intense, web of mistrust that characterized European oceanic travel. This mistrust was only exacerbated when expensive instruments were involved.

Part of the reason for this mistrust is that until at least the 1830s, the accuracy of instruments such as timekeepers to calculate longitude was being tested alongside a whole range of astronomical and navigational equipment. Testing the instruments, therefore, required an attempt at imposing order on voyages from places such as the state-funded Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Timekeepers on voyages of discovery were routinely accompanied by a Greenwich-trained astronomer, who also deployed a range of other instruments and techniques for measuring and testing longitude.

What’s more, managing the timekeepers was a very difficult process that demanded enormous amounts of work. Two sets of people carried out this labour: firstly, the astronomers themselves, who wrote in detail about the problems they encountered moving timekeepers on shore and manipulating them alongside the other astronomical equipment and instrumentation. On 15 November 1772, William Wales, an astronomer on Captain Cook’s second voyage, wrote that when moving the timekeepers on a small boat, a sudden jolt caused one of them the stop working.3

Source: Cambridge University Library, Royal Greenwich Observatory MSS (CUL RGO) 14/58, ‘William Wales Log Book from HMS Resolution’, p. 5v.

The second set of people entrusted with this labour was the workmen who carried out constant maintenance and repairs on clocks,the importance of whom is demonstrated in the following extract from the logbook of William Wales:

Image: Extract from the log book of William Wales Source: CUL RGO 14/58, ‘William Wales Log Book from HMS Resolution’, p. 40r

This passage conveys not only the material realities of moving such delicate instruments during voyages, but also the difficulties of assigning blame when things (inevitably) went wrong. The relationship between instructions, movement and blame was keenly felt by all members of a ship’s crew. Indeed, right through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European sailors crewing ships headed into the Southern Hemisphere took part in the important ceremony of ‘crossing the line’, marking the passing of a ship over the equator. Sailors who had previously crossed the line sought to conduct this ceremony for those who were entering the Southern Hemisphere for the first time. The ceremony usually involved the character of Neptune coming over the stern and quarterdeck in procession with his court. As Greg Dening has described: ‘[Neptune] would perform some farcical charade of the officers’ navigational tasks and declare that the ship had infringed on his domain. A mock trial of those guilty of the infringement would then begin. The trial was full of insults, injustices, erotic oaths, and compromising choices. A novice, for example, would have to choose between shouting “God save the King!” and getting shaving cream shoved down his throat when he opened his mouth.’4

Officers, and of polite rational European society in the late eighteenth century, were often extremely hostile to these crossing the line ceremonies. Diderot, in his entry on the ‘Baptism of the Tropics’ in the Encyclopaedia, described the practice as an abhorrent and ridiculous ceremony. Captain Bligh, of the infamous mutiny, described it as inhuman and brutal. But there was important meaning behind the ritual. It marked not just the movement between northern and southern hemispheres, but also the brutal forms of naval discipline and coercion inflicted upon the labour force to get ships to the equator and beyond.

The line crossed by European vessels was important because it meant anticipating and crossing into a future time and place, in which the meanings of the European world could be undone. One important way of undoing voyages was in the form of mutiny. In April 1789, Captain William Bligh (who went on to join Captain Cook for his third voyage of discovery) was forced by a large number of his ship’s crew into a small cutter, a thousand miles West of Tahiti.

Following the insurrection, the mutineers, with a stolen cargo of surveys, sextant and timekeeper, did what from a global perspective meant ‘going off grid’ – they located an island uncharted by Europeans and burned their ship.

A persistent claim for why longitude mattered for European sailors is that without it they were especially subject to being shipwrecked: without special hardware like time-keepers, sailors could not know ‘where they were’. But as Andrew Cook has pointed out, longitude mattered for East India Company captains not to prevent shipwrecks, but rather to ensure that officers knew when to turn north from a particular easterly point after rounding the Cape of Good Hope, in order to catch the monsoon winds to carry them northwards. With no land and little else to help co-ordinate direction, knowing one’s longitude was thought to be essential at this moment so that ships would not miss the winds. Missing the winds would delay the ships’ return to Britain with their expensive cargos, which could result in a massive commercial loss for their backers. If such an incident occurred, the ship’s crew would be asked to account for where they had gone wrong: by showing an account of the ship’s route in the form of a log book and journal, it was hoped the degree of failure and accountability could be calibrated.

For captains of voyages of discovery like Cook, the need to imagine timekeepers as a ‘trusty friend’ was equally vital. In order for Cook to claim his trip had been a success, the charts, logs and narratives of his voyage had to be trusted. When Cook delivered his paperwork back to the Admiralty after his voyage, his degree of success had to be calibrated against whether or not he could be trusted in what he said: did what he say happened really occur? The fate and use of expensive instruments like timekeepers were part both of his claim to be trusted and of the Royal Navy’s testing of that claim. The use of precision instruments like timekeepers, therefore, was less about getting things to go where they had to, and more about providing some way to gauge failure when they did not.

The danger in global approaches to history is that the use of technology in these accounts typically privileges and narrativises the ambitions of power. A global approach to history, as I reckon, has a real potential to counter this privileging of power. By going against the grain of narratives that have typically appropriated science and technology in the service of legitimation, the constant struggles and negotiations of marginalised and invisible groups can be revealed.

Writing global history does not necessarily mean that, simply by the power of the term ‘global’, different forms of history will be told. It runs the risk of merely capitulating to imperial and hegemonic power, and writing out exactly those groups we need to re-imagine. The virtues of a global approach must surely lie in our ability to think past those so-called globalising forces, and uncover all the forms of agency and struggle that existed and still exist, despite the apparent functioning through time of ‘global movement’.

Footnotes

1Philip Steinberg, The Social Construction of the Ocean (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001): 208.

2J.C. Beaglehole ed., The Journals of Captain James Cook on his Voyages of Discovery. Volume II: The Voyage of the Resolution and Adventure 1772-1775 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): 723.

3Cambridge University Library, Royal Greenwich Observatory MSS (CUL RGO) 14/58, ‘William Wales Log Book from HMS Resolution’, p. 5v.

4Greg Dening, Mr Bligh’s Bad Language: Passion, Power and Theatre on the Bounty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).