by Dr. Emily Michelson, University of St. Andrews

This article (Past & Present 235) took shape in a world that has now faded: I started it with a different set of intellectual priorities, and at a stage of my life that has since ended. But for all that, its value is greater in the new world it now inhabits.

When it began, this was almost, though not quite, a vanity project. When I first discovered the lone volume of conversionary sermons to be published in the 16th century, I was hard pressed to ignore it. I was not only finishing a book on Italian sermons and preachers grappling with interdenominational angst during the Reformation, but I had also studied Jewish rabbinic texts for a couple of years before pursuing a PhD. The conversionary preacher, Evangelista Marcellino (I knew him from his other sermons) walked lines I could recognize, though in a far different context. For a while I wanted to avoid writing about conversionary sermons. It seemed too pat and inevitable for someone with my training, and too narrow a step from my first book. But more and more examples of conversionary sermons turned up, and so did records of the Christians who wrote about viewing them. Reading them profoundly rekindled broader questions that had concerned me for a long time, primarily about the power of public religious spectacle; this article begins to address them. I later found another preacher, a century after Marcellino, who left written lists addressing the same questions I had – one of them was entitled “Why Public Conversionary Sermons Should Still Take Place, and Why Christians Should Attend and Watch Them.” When I saw that, I thought he might as well have written my name on his parchment, ideally with a pointy manicule: Your Project Here. I knew then that there was good material for both an article and a book, and that I wanted to be the one to write it. So this was at first a personal endeavour, borne of my own interests and competencies, even though from the outset I believed it would have broader import for the deep history behind Catholic-Jewish dialogue and interfaith relations. It felt like the right project for me to take on, but not necessarily like a crucial one.

The Past&Present article also has personal resonance for me because I clearly recall working on it the day my youngest child was born. I had met my imminent deadlines and gone on maternity leave, with time to stock the freezer and organise the house. Still no baby, so I reopened the laptop, thinking it was a good time to tinker with the notes for my ‘someday’ article, which I had tidied up to leave for a distant ‘later’. I put in an hour or two in the morning; the afternoon went differently. This month, when the article has finally seen publication, that baby is five and a half. (For my own sense of pride, I should point out that in the interim I also finished and published various other projects, large and small.) The era when children did not outnumber adults in my household (and when colleagues did not raise their eyebrows at my having three children), is long past. And as a result, I have since become more focussed on the distant future, the one I will not see but my eventual grandchildren might.

And in the era between the time I first drafted the article and its final publication, we have all moved sharply into a new political world: The treatment of marginalized peoples, and indeed, the shifting locations of those margins, are current and burningly important questions. In my beloved native country, long-time residents are forcefully deported, sometimes violently and with no explanation; the governing elite systematically tries to dismantle any legislation that prizes empathy for those unlike themselves (in looks or circumstances). In my beloved adopted country, the Brexit vote has forced the question of just how ‘foreign’ we want foreigners to be, and whether we or should truly separate the foreign from the domestic.

Rome’s Jews provide a valuable model for these problems. They were both natives and foreigners; “intimate outsiders” in Tom’s Cohen’s useful phrase. As this article points out, Jews had been in Rome continuously since before the dawn of Christianity itself. But the decades with which my article is concerned saw a clear and deliberate shift in Rome’s policy towards Jews. Where they once had been fairly well (though not entirely) tolerated, accepted, and integrated (unlike elsewhere in Europe), they were now segregated, deliberately impoverished, and more thoroughly derided. Other minorities, less well rooted in the city, suffered from similar treatment. As Marina Caffiero has suggested, Roman Jews, through a process of small redefinitions and legislations, found their status gradually altered; they were reimagined as heretics, and so put under the supervision of the Holy Office. Once native Romans, they were recast as legal outsiders.

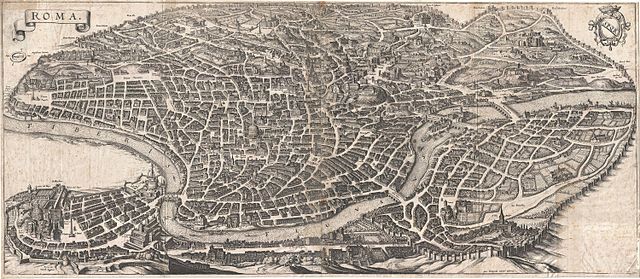

Merian, M., Topographia Germaniae, 1642., via Wiki Commons

Indeed, take the case of one of my preachers, the grandchild of converts. Born at least thirty years after his family left Judaism, and raised in a devoutly Catholic home, he was nonetheless labelled “the only converted Jewish preacher of the seventeenth century” in an article as recently as three years ago. To be fair, I think the author may have confused ‘grandchild’ with ‘nephew’ (they are the same in Italian) and did not do the math or the research to see that this preacher could only ever have considered himself Catholic; he was a pillar of the Dominican community in Rome for 40 years. But the fact remains: through an act of sloppiness or indiscretion, the status of this consummate Catholic insider is still subject to obfuscation, inaccuracies and generalizations still projected onto him because of his Jewish roots. My article argues that conversionary preaching became a sort of vortex that absorbed a wide and contradictory variety of Catholic ideas about Jews. Much anti-Jewish policy in Rome reflected, more than anything else, these imaginings and projections.

Its later history only makes conversionary preaching seem even more germane to today’s debates. While this article only addresses the 1500s, conversionary preaching extended into the eighteenth century and remained on the books until the era of Italy’s unification. Over time, the format and persistence of conversionary preaching itself became a subject of sermons. In the second half of the seventeenth century, the same preacher who wrote those lists also devoted a sermon to asking why conversionary preaching was preferable to disputations – the time-honoured medieval form of oral polemic. Speaking to an imaginary Jewish interlocutor, he argued against disputation: “You would like a Jew and a Christian to preach in turn; the Jew against the Christian religion and the Christian against the Mosaic rite. In that way, they would be equal.” The sermon rejects entirely the possibility of a two-speaker disputation. “I respond that this cannot be permitted…You cannot treat as equal truth and lies… a prince must, in his kingdom and dominion, have the truth be preached, and certify that what follows is true, and prevent the preaching of what is false.” The sermon calls the “Mosaic cult” deadly for those who continue to profess it, and seeks to silence its representatives.

This form of argumentation has stayed with us. Antisemitism never goes away, of course, but more broadly it’s also the preacher’s technique in this sermon that is pertinent here. He refused to give a hearing to a position he considered not only repellent, but harmful. This approach represents a shift in religious debate from the disputations of the Middle Ages. Indeed, in making this argument the preacher is in fact confirming the position of modern scholars of medieval disputations, some of whom argue that the very act of disputations seemed to validate the fundamental similarities between Christians and Jews. This sermon encapsulates the rancour and intolerance of so many post-Reformation religious institutions in Europe. But its author’s 17th-century position remains entirely current today; we call it no-platforming, and as a technique it is still much debated.

Much of the rancour of our own era echoes his. The religious polarization of early modern Europe presages the polarizations of our own. Indeed, for early modern preachers, the stakes probably seemed even higher than they do for us. For the most part, our own convictions, however strongly held, primarily concern the fate of the living; for preachers in the early modern world, in contrast, any soul they failed to save faced damnation and hellfire for all eternity. Their road to any kind of respectful interaction between faiths was very narrow, with precipices on each side.

Then again, the stakes feel plenty high to us today. What does my article offer to our own fraught society? In it, I try to show how fears and concerns specific to early modern Rome were projected onto Jews, who suffered largely because of the preconceptions of others. It examines the ways that Roman Jews were despised less for who they were than for what they symbolized. But it doesn’t take much imagination to see that the groups most targeted today are equally victims of unjust projections, specific to the circumstances. With this article and the broader project around it, I want to make it clear just how entrenched are the layers of misunderstanding, false labelling, and stereotyping, built up over centuries, that continue to colour the vision of even the best-intentioned among us. This no longer feels like a private endeavour, but a global one of tremendous urgency, and one small way to address the problems of the world my children will inherit.

Dr. Michelson’s article “Conversionary preaching and the Jews in early modern Rome” can be found online here.

St Peter’s Square, Vatican City, image courtesy of “Diliff” (2007), via Wiki Commons