by Dr. Patrick Luiz Sullivan De Oliveira (Singapore Management University)

Back in 2012, during a break in my first year of graduate school, I found myself in my father’s travel agency in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. I remember stressing out over a thesis topic. I was planning to write about the creation of old cities in nineteenth-century France (the historical districts we know today as vieux Lyon, vieux Marseille, etc.) but was worried that the topic was overcrowded. I browsed through the bookshelf in his office as I vented (Figure 1), tracing my fingers over the spines of management tracts and history books (he’s always been a businessman with a humanist bent). One book in particular caught my attention: Peter Hoffman’s Wings of Madness: Alberto Santos-Dumont and the Invention of Flight, a popular biography of the Brazilian aviator published by an accomplished science writer in 2003. “This might be a fun read,” I thought to myself as I pocketed the book.

Figure 1. Author’s father’s travel agency in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. image by Luiz Carlos De Oliveira

A year later I was back at Princeton. I had just completed my general exams and anxiety levels concerning the thesis had reached new heights since, well, I now had to start working on it. I was certain about abandoning the “old cities” project. I had just finished up an article on the invention of vieux Lyon and didn’t think I had much more to say (reflecting back on it, I probably do, but wasn’t ready for it). I toyed with different projects by browsing through library catalogues, online archives, and running ideas through my mind in sleepless nights. At breaking point, I realised I needed to take a break. That’s when I returned to Wings of Madness.

Hoffman’s book was entertaining. Although it lacked analytical depth, it was precisely the kind of riveting narrative I needed. It also made me wonder: why did Santos-Dumont choose to go to Paris to conduct his experiments with flight? After hashing out with my advisor and mentors, I realised that I had the beginnings of a research question. I set out to do archival research in France with the goal of explaining why Paris became the global capital for aeronautical pursuits in the last third of the nineteenth century (a question that has evolved as I continue to work on this topic).

Santos-Dumont is a significant part of that story, as the article I have written for Past & Present argues. Although most Brazilians would disagree, he did not invent the airplane. Nor was he the first to fly one. Where Santos-Dumont did excel was in making a spectacle of his lighter-than-air experiments. His Parisian ascents aboard balloons and airships were highly mediatised events that popularised the idea that a world permeated by flight was possible in a time people were still very sceptical of aeronautical pursuits.

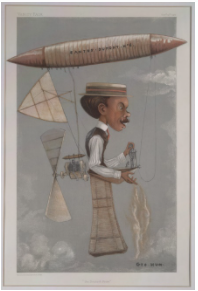

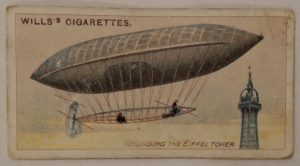

“Le petit Santos,” as Parisians affectionately called him, skillfully worked with the press to become the first global aeronaut celebrity. Huge crowds gathered to watch his flights, and the mass illustrated press, which was just coming to its own, eagerly represented these events (Figure 2). His aircrafts and image stamped the cover of magazines like Vanity Fair and all types of advertisements, like this Will’s Cigarettes trading card, which I snagged at a marché aux puces in Paris (Figures 3 and 4). All of this helped crystalize Paris’s global image as a spectacular center of what I term “technological cosmopolitanism”—a worldview that emphasised technology’s potential in facilitating exchanges and unifying people around the world.

Figure 4. A trading card that came with Will’s Cigarettes featuring Santos-Dumont’s No. 6 rounding the Eiffel Tower. Author’s collection.

But this is only part of the story. As I kept researching Santos-Dumont’s celebrity, I started wondering who was included and excluded from the visions it projected. I was intrigued by how much of the French and American press construed him as French, even though he was from Brazil. This prompted me to look at Brazilian archives, and I discovered that many Brazilian authorities and journalists resented the French appropriation of Santos-Dumont.

Members of the Brazilian elite saw in Santos-Dumont a powerful symbol of their country’s progress—something they were especially concerned with in order to cleanse Brazil’s association with chattel slavery. In fact, the myth of Santos-Dumont performs this ideological service to this day, as seen by a recent HBO miniseries’ sanitised portrayal of his childhood in Brazil in the final years of institutionalised slavery (he was born in 1873 and slavery was only abolished in 1888). Rather that reproducing this clichéd image of Santos-Dumont representing a break from a pre-modern barbaric regime (as the republicans who came into power in 1889 would often frame it), I became interested in continuities. After all, the fortune Santos-Dumont used to go to Paris and fly above its boulevards came from his father’s immense coffee plantations—plantations that at one point were maintained by enslaved labour.

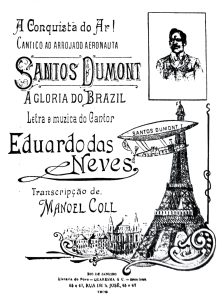

As such, I decided it was important to recenter Afro-Brazilians in this story. This, of course, meant recognizing the economic role their enslaved labor played in establishing the material conditions for Santos-Dumont’s aerial adventures. But it also meant looking into the irony of how emancipated Afro-Brazilians engaged with the celebration of a wealthy white Brazilian whose image authorities mobilized to present Brazil having parity with European “civilisation” That’s because rather than accepting the use of Santos-Dumont’s celebrity as a technique to whitewash history, Afro-Brazilians like the street singer Eduardo das Neves appropriated it in order to reassert their place in this story. Neves, who adopted the stage name “crioulo Dudu”, was one of many black performers who drew from the cultural streams of what Paul Gilroy termed the “Black Atlantic” to produce self-consciously modern forms of urban entertainment—individuals like Cuban Rafael Padilla, who took on the name Chocolat and became an entertainer in Paris. Neves composed a song celebrating Santos-Dumont’s feats that became one of the most popular tunes in the First Brazilian Republic—an example of how Afro-Brazilian’s were major contributors to the construction of national identity despite the deep-racism that permeated Brazilian society and institutions (Figure 5. You can also listen to a rendition of the song by another artist on YouTube).

Figure 5. Eduardo das Neves, ‘A Conquista do Ar’ (Rio de Janeiro, 1909). Courtesy of Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM 95-8342).

Ultimately, the research into Santos-Dumont’s transatlantic celebrity proved to be a fruitful avenue to explore the complex ways in which technology gets mobilised in the imagining of communities. By appropriating Santos-Dumont, the French sought to retain their dominance in aeronautical science and assert their universalist pretensions. Brazilian authorities and elites embraced him as a sign that the country was at the vanguard of progress, although that vision was limiting in the sense that it reproduced Eurocentric biases. But popular culture could also be an avenue for those who were marginalized from these visions to practice resistance and self-assertion, as seen in the case of Neves.

This is also why I became so enthralled by Tarsila do Amaral’s painting Carnaval em Madureira (Figure 6). It is based on an actual event, when residents of one of Rio de Janeiro’s poor and peripheral neighborhoods built their own model of Santos-Dumont flying his dirigible around the Eiffel Tower for the 1924 Carnival. But what’s truly fascinating is how Tarsila, the most impressive of the Brazilian Modernists, went about producing a more inclusive vision of technological cosmopolitanism. Allow me to quote from the article:

Tarsila’s modernity, inspired by Santos-Dumont’s feat and its reimagining by marginalized Brazilians,is a syncreticmodernity — it includes the North and the South, the technological avant-garde and the vernacular of everydaylife. In the nineteenth century, the bounded labour of Afro-Brazilians helped constitute the fortune that allowed Santos-Dumont to go to Paris and become a celebrity aeronaut. In the twentieth century, Tarsila depicted descendants ofthe enslaved appropriating the vision of technological cosmopolitanism that Santos-Dumont’s celebrity had helpednurture and making it their own, just as Neves had done. If the ‘crioulo Dudu’ represented the agency of Afro-Braziliansstruggling to reinsert themselves into turn-of-the-century cosmopolitan visions, Tarsila represented the willingnessof avant-garde elites to widen the boundaries of cosmopolitanism. The paintingsignals that modernity was notsimply an imperious projection from Europe, but the very thread thatconnected and enabled these variegated transatlanticexchanges and experiences.

Figure 6. Tarsila do Amaral, Carnaval em Madureira, 1924, Oil on canvas, 76 × 63.5 cm. Acervo da Fundação José e Paulina Nemirovsky, em comodato com a Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo.

Next time I return to Belo Horizonte, I should probably return Wings of Madness to my father. More important, though, is my plan to bring along a print of Tarsila’s painting for him to hang in his office. Although the pandemic has rendered it a depressingly quiet space for the past two years, I hope that it will soon be buzzing again, and I envision the colorful print prompting conversations about more inclusive and truly cosmopolitan technological stories.