by Prof. James Vernon (University of California, Berkley)

These are odd times to be reading and writing about Heathrow. The Age of COVID has reduced passenger numbers by a staggering 72% to levels not seen since the Oil Crisis in the mid-1970s. That crisis led the government to shelve plans for a third London airport for a decade. This year the planet has had some reprieve as COVID has compelled an airport still seeking to build a third runway and more terminals to operate on just one runway and three of its five terminals. It is workers in the aviation industry that are once again made to pay the costs as massive mutlinationals worry about collapsing profits and falling share prices. British Airways, whose recently retired CEO has made £33million in salary, bonuses and pension payments since 2011, plans to make 12,000 of its 42,000 workers redundant. It has already laid off half that number, many of them cabin crew. Heathrow, whose major shareholders include the sovereign wealth funds of Qatar and Singapore as well as the UK Universities Superannuation Scheme, has 4,700 employees. The airport has proposed pay-cuts, early retirements and threatened section 188 notices that would allow them to fire and rehire them with worse pay and conditions if agreement is not reached with the unions.

London Heathrow Airport from the air, by Konstantin Von Wedelstaedt (August 2009), via Wik:Commons used under GNU Free Documentation Licence 1.2

We at least get to hear about the plight of those workers. Much less is heard about those mainly non-unionized and largely invisible workers employed by the companies to whom cleaning and catering services are outsourced to. Many of these workers are BAME Britons who live around the airport in Hounslow, Ealing and Hillindgon. We do know that two thirds of those once employed by the catering firm Do & Co at Heathrow were made redundant this year. The Labour leader of nearby Hounslow council has suggested the decimation of the airport’s outsourced ancillary services has made his town resemble former mining towns in the 1980s with over 40 per cent of its population on government support.

And, of course, COVID has decimated the communities surrounding the airport all of which have large BAME populations. With disproportionately high numbers of BAME Britons dying of COVID and employed as key workers providing essential services, the Age of COVID has taught us once again that capitalism is always racialized and can often be genocidal. Bodies of color are allowed to die so they can provide services that enable white bodies to live and the economy not to be shut down.

In my article for Past & Present ‘Heathrow and the Making of Neoliberal Britain’ I tried to excavate some of the history of our grisly present. In particular, the article foregrounds the plight of workers of color, mostly women, who were hired by the companies to whom cleaning and catering services at the airport were first outsourced to in the 1960s and 1970s. At one level my aim was simply to make these workers visible and to ask what their long overlooked working lives can teach us about the racialized forms of neoliberal capitalism at the airport.

The piece makes two interventions. In the first place it seeks to demonstrate that some of the forms of privatization, deregulation and outsourcing that came to be associated with neoliberalism from the 1980s were a feature at Heathrow from the 1960s. This is less an argument about periodization, an insistence that neoliberalism has a longer history than we conventionally allow, than an attempt to highlight how some of its constitutive practices developed within the system of welfare capitalism associated with social democracy. I identify the creation of the British Airports Authority (BAA) in 1965 by the Labour government of Harold Wilson as a decisive moment. As a semi-autonomous but government funded quango BAA was charged with making the airport profitable by increasing revenue from its duty free retail trade and cutting labor costs. It was allowed to outsource retail, security, catering and cleaning services to companies not bound to employ unionized workers. Needless to say, in an uncanny echo of the crony forms of neoliberal capitalism at work in the Age of COVID, where friends and associates of government ministers are awarded lucrative contracts for vital (but frequently undelivered) services in the battle against the pandemic, it was the often well-connected bosses of companies like Forte Holdings, Securicor, and Pritchard Service Group that harvested these new service contracts.

Airport Cleaner, by Peter van der Sluijs (2013), via Wiki:Commons used under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2

Secondly, it explores the racial and gendered politics of this shift. Where once Heathrow had been a cathedral for the labor of unionized, white, working men, the precarious and cheap forms of outsourced labor at the airport, particularly in back-office roles like catering and cleaning, were increasingly performed by Commonwealth citizens of color many of whom were women. Here I emphasize, in ways that may perhaps soothe those who worry neoliberalism is an analytic used to explain everything, that we can not understand the changing forms of racial capitalism at the airport in the 1960s and 1970s without attending to how decolonization shaped Britain’s post-imperial social formation. Paradoxically, as the airport became dependent upon the cheap labor of predominantly South Asian women who had settled locally in places like Southall and Hounslow, it also became the frontline of a hostile immigration regime that sought to exclude them and insulate Britain from the obligations of empire. Despite the iconic image of the Windrush and narratives about its ‘generation’, by the 1960s most Commonwealth citizens arrived in the motherland by plane at Heathrow. It was in the airport that Britain’s border was most callously and violently policed.

In the article I use the analytic of racial capitalism to make sense of this conjuncture when racialized forms of outsourced labor and hostile immigration regimes at Heathrow came together in the 1960s and 1970s. It was a term first developed in the 1970s by South Africa marxists seeking to understand the peculiar forms of capitalism in an apartheid regime, then deployed by Cedric Robinson to claim that long before slavery and imperialism capitalism in Europe had always been racialized, and in recent years used to theorise contemporary forms of racial subjgation by the Black Lives movement.

Had the pandemic not interrupted my research I would have liked to spend more time working on how the employment and immigration practices at Heathrow informed new analyses of the intersections of race, class and gender within black and feminist politics of the 1970s. In the mid 1970s the Race Today Collective published a number of pieces highlighting both the plight of Asian women cleaners and the growing business of detention and deportation at the airport. Although he did not use the term, Ambalavaner Sivanandan, Director of the newly radicalized Institute of Race Relations used its journal Race and Class to develop an analysis of how the immigration regime and the racialized division of labor restaged the forms of racial capitalism under colonialism in a post-imperial Britain. Sivanandan was in conversation with Amrit Wilson whose seminal Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain, published by Virago in 1978 and recently reissued, provides an important gendered reading of the colonially marked but new forms of racial capitalism in Britain. Much of the material outlining the conditions of work for people of color at Heathrow came from the archive of the Institute of Race Relations, and it was there, in conversation with Sivanandan, that Cedric Robinson published in Race and Class and wrote part of Black Marxism. At the same time Stuart Hall was also engaging with the concept of racial capitalism in his classic essay “Race, articulation and societies structured in dominance”. We need more work on this critical moment in the transnational formulation of the concept of racial capitalism and its use by black British intellectuals to make sense of Britain’s post-imperial social formation.

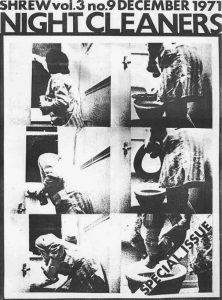

Finally, there is also more work to be done on the role of feminists in theorising and organising for the women of colour who were on the frontline of the new forms of outsourcing. The now conventional line, which I reproduce in the article, is that the Women’s Liberation Movement could not overcome it’s predominantly white and middle class privilege as evidenced by their limited success in organising nightcleaners in London in the early 1970s. I have only recently been able to access both the recently reissued Nightcleaners (1975) film by the Berwick Street Film Collective and some of the materials produced by the Cleaners Action Group, which included Sheila Rowbotham and Sally Alexander, in Shrew, Red Rag, Spare Rib and the Cleaners Voice that comes with the box-set. I was immediately struck by the parallels with Heathrow. In 1968 the cleaning of government buildings had been outsourced by the Wilson government. As contracts were renewed every two years a plethora of companies, including Pritchard Services, competed to undercut their rivals by reducing labor costs in the kind of race to the bottom of working conditions that is now so familiar.

Nightcleaners (1975) – Excerpt #1 from james scott on Vimeo.

Yet the more I learnt the more I regretted echoing the critiques of feminists for not being more successful at organizing and theorizing intersectionally. Certainly the Cleaners Action Group had far too little to say about race given that many nightcleaners were women of colour from the Carribean and South Asia (as well as migrants from Ireland, Greece and Spain). Yet they made remarkable efforts to comprehend and represent the plight of women who return from poorly paid work at 6am to begin an unpaid double shift at home for their children and husbands with just a few hours of sleep. If their campaign ultimately failed to improve the working conditions of these women this was not necessarily a consequence of their own politics. Organising a workforce largely disowned by a masculinist trade union movement, fractured by multiple employers, and working in a multitude of buildings spread across London was an almost impossible task.

Poster for Nightclearners (Berwick Street Collective, 1975), image via imbd, a DVD of the film can be obtained here.

Nightcleaners is literally a film about whether it is even possible to represent these women and their paid and unpaid work. Frequently during the 1970s the questions of how to theorise racial capitalism, and how to organize those women of colour who were at the forefront of its new forms, also became a question of how to document their lives and represent them. There was an amazing proliferation of work by artists, invariably organized as collectives, in the 1970s exploring these questions in conversation with the Women’s Liberation Movement. We see this in the image I use in the article produced by Paul Wombell and the feminist Poster Collective. After Nightcleaners some members of the Berwick Street Film Collective made an equally powerful film, which has also been reissued, 36 to 77 about the life of Mrtyle Wardally, one of the subjects of Nightcleaners, born in Greneda in 1936. Mary Kelly, another member of that Collective, worked with Margaret Harrison and Kay Hunt on an installation Women and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry 1973-75 restaged at the Tate in 2016. The Hackney Flashers photography collective, part of whose archive was been uploaded to a website in 2014, also staged an exhibition on Women and Work in 1975 that explored the great variety of paid and unpaid labour done by a diversity of women in Hackney. The See Red Women’s Workshop has finally had many of its iconic posters published as a collection including Black Women Will Not Be Intimidated that foregrounds Heathrow and the protests there by Awaz, OWAAD and Southall Black Sisters against the infamous virginity testing of Asian women. Now that this work is being returned to we can start to assess its important role in making visible the shadowy netherworlds of racial capitalism as it was reconstituted in post-imperial Britain.

It was on the shoulders of these black and feminist activists, intellectuals and artists that I stood in writing this article. Even as we celebrate the University of London ending the outsourcing of its cleaning staff after a seven year campaign, there remains a lot more work to be done to make visible and comprehend the struggles of those who preceded them.