by Dr. Song-Chuan Chen (University of Warwick)

Located in Taipei, the voluminous records on tomb protections in the Academia Sinica archives, piqued my curiosity. It was 2009, and I was leafing through a collection of Qing dynasty foreign office documents when my attention was arrested by accounts of Chinese villagers ardently protecting ancestral tombs against Western encroachment during the closing decades of China’s last dynasty.

The villagers’ tears and protests against tomb destruction conjured personal memories of growing up on a remote outer island of Taiwan in the 1970s and 1980s where an old evolving tradition of ancestor worship escaped the disruption of modernity. In those days, my mother faithfully prepared annual rituals of ancestor worship during important festivals, and my father careful maintained his father’s tomb, to which he has a deep attachment. To him, the tomb provided a physical connection to his father, whose remains lay just beneath the earth. Because my father and brother believed that my career was not going anywhere (in fact I have been not a day without employment even before graduation), they sought to improve my fortunes in 2011 by trimming the overgrown Acacia trees surrounding the burial site. In their minds, the tomb’s feng shui holds a particular significance to my life. At the same time and entirely by coincidence, I was in Bristol writing the paper “The Power of Ancestors” and thinking more about obtaining a permanent teaching position. Even though my family and I are half a world apart, the completion of my PhD deepened their belief in feng shui. I allow them—and myself half-heartedly—to maintain this belief system that I have known my whole life merely by growing up in that world.

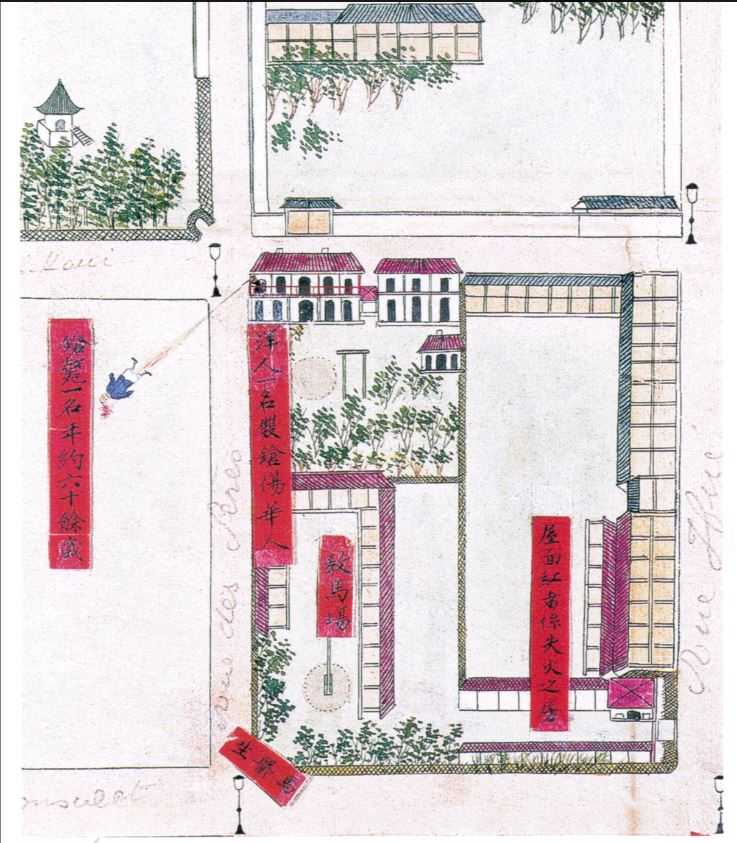

This map by an unknown Chinese artist of the nineteenth century depicts the 1874 incident in which Chinese protesters were gunned down by French policemen. (Picture source, Collectif, Le Paris de l’Orient : Présence française à Shanghai 1849-1946, Musée Albert Kahn, 2002, 44

The title “The Power of Ancestor” had different origins altogether. When I finished reading the thousand pages of archival materials that I had gathered, an image came into mind that encapsulated how I imagined villagers across China fighting against foreign encroachment to protect ancestral tombs during the second half of the nineteenth century: The Army of the Dead in the movie The Lord of the Rings. These ghosts of the White Mountains, cursed to dwell in the cold and darkness, were summoned by Aragorn, the Heir of Isildur, using a sword re-forged by elves that allowed him to command this soulless army. Swiftly levelling battlefield enemies to lift the siege of Minas Tirith, the ghost army was vital to Aragorn’s victory. No sooner was the battle won than he released them from their curse. The story helped me visualise how tombs, ancestor worship, and the concept of feng shui played a role in China’s foreign relations. The deceased Chinese, while nowhere near as powerful as the ghost army of the White Mountains, succeeded in assisting the Qing patriots in expelling Westerners from tomb land.

The more I have researched this history, over seven years on and off, the more I have realised how the Qing’s bureaucratic officials, who were the most talented men of the Qing empire, played a key role in limiting the power of the ancestors. They were no Aragorns. Their weapons were not swords but brush and ink. Rather than summoning the power of the ancestors as a weapon, they negotiated peaceful interactions between the village believers and the foreign community—and thus dissipated the latent force that stemmed from the belief system.

The power of ancestors has subsequently been subjected to modernity’s onslaught in the twentieth century. Yet, the ghosts of the ancestors live on. Even though tombs in China under the communist regime have experienced greater destruction than ever before, the religious system is alive and well—and edging its way into urban space and modernity in unimaginable ways of reinvention. It was not what it was, but it is as it has always been.