by Dr. Samantha Iyer (Fordham University)

The United States’s food stamp program is under attack again—again. The current government shutdown has left the nearly 42 million people who rely on the program—now called the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, or SNAP—in a state of uncertainty. Even more fundamentally, in July of this year, Congress passed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which is bound to significantly reduce the number of people who can benefit from the program. That is because the bill increases the state and local costs for administering SNAP, expands the work requirements for receiving assistance, and excludes a range of non-citizens from eligibility. The contraction of government assistance programs is nothing new. It is most often associated with welfare reform under the administration of Bill Clinton in the 1990s. But family food assistance programs have followed a somewhat different trajectory than other government assistance. That trajectory makes the current cutbacks all the more dangerous. For as US policymakers have slashed other welfare programs, these food programs have come to serve as welfare of the last resort.

I examine the distinct path of family food assistance programs in a recent article, ‘Agricultural Workers, Tenant Farmers, and the Midcentury U.S. Welfare State: A View from the Lower Mississippi Valley’ Past & Present No. 267 May 2025. It is often forgotten that the early history of these programs began in the agrarian United States. In both their conception and their execution, they were primarily supposed to serve large commercial farmers rather than the recipients of the aid. The objective of the commodity distribution program created in 1935 was to get rid of food crops that the federal government had bought up to support crop prices—a strategy of disposal that would only later be supplemented by others, such as the foreign food aid program. Agricultural workers and tenant farmers were also among the chief recipients of surplus commodities and, later, food stamps. For them, the programs offered what the National Sharecroppers Union called “ex post facto aid” from the very beginning. Scholars have often argued that agricultural workers and tenant farmers were excluded from the New Deal welfare state. Yet these rural residents did in fact rely heavily on government assistance. It simply took the form of food, under programs that reinforced the racial and class power of white landlords and employers.

What I found from examining petitions, testimonies, oral histories, and government records was that the commodity distribution program absorbed features of the old furnish system of credit in cotton-producing regions of the Mississippi Valley. Under that system, tenant farmers and agricultural workers borrowed food and other commodities from landlords, employers, and merchants at the beginning of the harvest season. They then repaid it at exorbitant interest at the end of the season in the form of a portion of the cotton crop. As mechanized and petrochemical-based faming came to overtake labor-intensive forms of production, the commodity distribution program continued to give landlords and employers power over the subsistence of displaced or underemployed tenants and agricultural workers. That power was now simply mediated by the county governments that administered food assistance programs and in which white planters held much power. Thus, for instance, many counties denied residents food assistance during the seasons in which planters most needed agricultural labor.

Established in 1964, the food stamp program that gradually replaced surplus commodity distribution only reinforced these patterns. It did so through the regular budgeting practices that it demanded. Until 1977, people eligible to receive food stamps had to purchase them, and to do so, they initially had to pay a minimum amount in one lump sum each month. That requirement was at odds with the variable temporal pattern on which tenant farmers and agricultural workers actually earned and spent their cash: It was difficult to save up enough to buy a whole month’s worth of stamps at one time. Counties that transitioned from surplus commodities to food stamps thus saw participation rates rapidly drop. Those who did enroll in the program often had to borrow to buy their food stamps, a need that drove them back into the hands of creditors—often their employers or landlords.

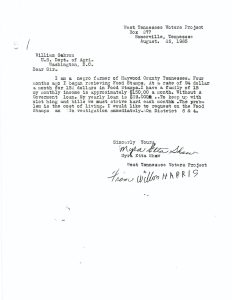

Myra Etta Shaw explains the struggle to buy food stamps for 94 dollars on a monthly income of only 150 dollars. Image Credit: University of Memphis Special Collections, MSS. 41, 2-44.

Activists in the Lower Mississippi Valley demanded a transformation of these programs, and their calls would reverberate to the national level. Beginning in Tennessee in the late 1950s, a succession of rural counties ended their surplus commodity programs in retaliation for efforts by civil rights organizations to register Black voters. In response, local activists set up alternative systems of food distribution and demanded that the federal government step in to distribute surplus commodities. The activists also criticized the punitive nature of the food stamp program and called for a structural transformation. In 1966, tenant farmers and seasonal workers led by Unita Blackwell, Isaac Foster, and Ida Mae Lawrence drove into and occupied an abandoned air force base in Greenville, Mississippi to demand that food and other welfare programs be led by low-income people themselves. The upheaval over food assistance in the region soon drew the attention of national civil rights organization as well as senators like Joseph Clark and Robert Kennedy. This chain of events led to major reforms of federal food assistance programs under Presidents Johnson and Nixon, reducing the cost of buying food stamps and giving households greater flexibility to determine how much and when they bought them. Nonetheless, the punitive character of family food assistance never fully went away. The revised program imposed strict work requirements. And in contrast to cash assistance, food stamps are restrictive by their very nature because no one can live on food stamps alone.

In more recent decades, as cash assistance programs have shrunk in the United States, the food stamp program—renamed SNAP in 2008—has dramatically expanded. As of 2024, an astonishing 12 percent of the US population relies on food stamps. The mid-twentieth-century experience of agricultural workers and tenant farmers has in a sense become generalized as SNAP has come to offer welfare of the last resort for other populations. What the recent revisions to the program threaten to do is puncture the already thin and worn fabric of the social safety net that still remains.