Dr. Dan Haines (University College London)

For Jean Kingdon-Ward, the night of 15 August 1950 should have been ordinary. She and her husband Francis, a well known British botanist, were travelling in the borderlands between northeast India and Tibet, looking for plants. All seemed calm.

Suddenly, a huge earthquake shook the ground underneath their tent.

Jean wrote in her memoir, ‘I felt the camp bed on which I was lying give a sharp jolt . . . The realization of what was happening was instantaneous, and with a shout of “Earthquake!” I was out of bed’. Despite feeling many earthquakes during her years in the region, this was the first time she experienced ‘the uttermost depths of human fear’.

‘Incredibly’, she went on, ‘after an interval that can only be measured in terms of eternity, we found ourselves back in the more familiar dimensions of space and time’.

Frank also wrote about the experience. ‘I find it very difficult to recollect my emotions during the four or five minutes the shock lasted’, he wrote in the scientific journal Nature, ‘but the first feeling of bewilderment — an incredulous astonishment that these solid-looking hills were in the grip of a force which shook them as a terrier shakes a rat — soon gave place to stark terror’.

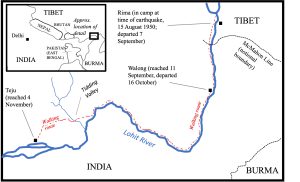

Map of the route that the Kingdon-Ward’s took on their botany trip following the course of the Lohit River. Map by Dan Haines, all rights reserved (2024)

In both accounts, the shock – which still ranks in the world’s top ten largest instrumentally-recorded earthquakes – made the landscape behave strangely, induced intense fear, and disrupted their sense of the normal passage of time.

When historians write about earthquakes, we usually focus on the aftermath and tell stories about the politics of relief distribution or arguments about reconstruction. Survivor testimony, like Jean and Francis’s, usually just features as an opening vignette to set the scene.

I wanted to take their experiences more seriously, and find out what it means for how we understand the way that disasters impact on people’s lives. The beginnings of a surprising answer comes from psychology research on emotions, specifically awe.

Psychologists describe awe as an emotional response to two triggers. The first is a sense of vastness, something much bigger than the individual who senses it. We might colloquially call this ‘wonder’.

The second is the problem of accommodation. Vastness is difficult to comprehend in one’s accustomed way of thinking, so the mind has to work extra hard to comprehend the experience.

Both the Kingdon-Wards spoke of the vastness of the earthquake in terms of its jarring sounds, sights and sense of movement. The disorientation they felt showed how much difficulty they had in accommodating what was happening

There’s more: some research links awe to a slowed-down perception of time. We already saw that the earthquake seemed to last forever to Jean. Francis, too, wrote in National Geographic that ‘The initial shock had lasted only four or five minutes. It had seemed an eternity.’

But for the Kingdon-Wards, the experience of the earthquake wasn’t over once the worst shaking ended. It stuck with them during their eight-week walk back down the Lohit Valley to the Indian plains.

During that time, the earthquake continued to shape their emotions and time-sense. In a detailed private diary, now in Kew Gardens Archive, Frank wrote constantly and touchingly of his worries for Jean. She suffered from depression, sleep-loss and bodily weakness that had no obvious physical cause. Aftershocks, which happened daily, always alarmed her.

Frank, for his part, was deeply afraid of heights, and the earthquake had destroyed bridges and caused landslips everywhere. The party had to inch along narrow pathways and clamber across loose rocks, all over steep cliffs and sheer drops.

View of the Lohit Valley from high ground, by Rajbhowmick, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As soon as the couple reached the Indian plains, though, their writings changed dramatically in tone. Frank’s diary suddenly began recording entertaining minutiae, like an encounter with a friend’s pet porcupine. Jean’s memoir, published soon events, described taking a flight back over the Lohit Valley as ‘thrilling and wonderful’. Fear and anxiety seemed long gone.

Emotions, then, were closely aligned to their sense of place. The memory of the earthquake haunted them for the rest of their lives, but it was the landscape of the ruined valley, and the sensation of aftershocks, that had made those emotions overwhelming.

What does this mean for how we understand historical disaster experience?

The way that the Kingdon-Wards wrote about time, emotions and senses was reflected in many other examples of earthquake survivor narratives. Some of these come from accounts of 1950 by Indian members of the Assam Rifles, a paramilitary group that patrolled the frontier. There were also many examples from South Asia from around the same period, some of which I explore in the book I am currently writing about the 1935 earthquake in Quetta (in what is now western Pakistan).

I’ve heard anecdotally from colleagues in Turkey that narratives of slowed-down time also circulated after the terrible earthquake there in February 2023. Soldiers who survived artillery bombardment during the First World War also described that experience in similar terms.

So, the sense of time can define histories of exceptional moments, highlighting what makes them different from the everyday course of life. Really understanding how it felt to people to live through disasters, and how and why those experiences stuck with them afterwards, is an important part of recovering the past.

Researching earthquakes has changed how I think about doing history. When I started, my project was supposed to be all about state power and anti-colonial politics after large shocks.

But the archives kept throwing people’s experiences at me. As well as affecting me deeply (one particular passage in a memoir forced me to hide tears in the British Library reading room), this made me realise that emotions are not just good for colourful vignettes. They shape what individuals pay attention to, what they value, and how they relate to others.

In my article for Past & Present, I explored the emotions of an earthquake without much regard to politics. In the book, if I get it right, I will synthesise the emotional and sensory history of earthquake experience with the story of the political contest between colonialists and nationalists. Newspaper columns and bureaucratic letters dealt in emotions, too.

I will leave you with a pleasant thought from Frank Kingdon-Ward’s diary. One of the last entries was from 6 November 1950. ‘A perfect day, almost cloudless blue sky’, he wrote. ‘The mountains seem far away’. For him, the earthquake was safely in the past. For us, his experience makes fascinating reading.