by Dr. Sonia Tycko (The Rothermere American Institute and St Peter’s College, Oxford)

Prison and detention center authorities around the world have begun to release some inmates in reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic, at the urging of prisoners’ rights activists. These releases seem to vary from the unconditional release of convicts who were already near the ends of their sentences, to the temporary release on bail or license of prisoners on remand or mid-sentence. With advocacy efforts and media attention focused on the decisions about release, little has been reported about what awaits prisoners beyond the prison walls. Historically, captors have often let captives go from hazardous disease environments. Past jailors’ methods and prisoners’ reactions can remind us that the mere fact of release—while clearly a crucial public health measure today—is not, in itself, enough. Prisoners should not be expected to be indiscriminately grateful for release. How prisoners are freed matters, and disease plays a major role in their experience of freedom.1

I briefly mentioned the effects of disease in my recent article, “The Legality of Prisoner of War Labour in England, 1648–1655” (Past & Present #246), which explains that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, prisoners of war were regularly “freed” to work for state-selected masters. Work release programs in US prisons today offer a striking contemporary parallel.2; During my period of focus, the Civil Wars and the First Anglo-Dutch War, prisoners-turned-servants went to work both near and far: in England, Barbados, and Massachusetts.

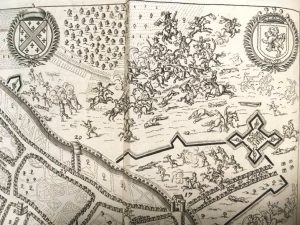

The Cromwellian forces at the Battle of Worcester captured thousands of Scottish soldiers. Many of these prisoners of war were subsequently released to work for private masters in England and English America. (Foldout map from Thomas Blount, Boscobel: or the Compleat history of his sacred Majesties … preservation after the battle of Worcester, etc., 1680 [first edition 1660]. The British Library, G.3552.)

Indeed, freedom from prisons likely improved prisoners’ life chances but at the same time, prisoners did not welcome their transportation to the English American colonies or the coercion of their labor. In fact, they ran away, refused to work, and even petitioned for protection from hard labor under the laws of war. One reason for prisoner resistance, which I did not explore in the article, was that their health, and that of the women and children who accompanied them, remained in danger in their new sites of work.

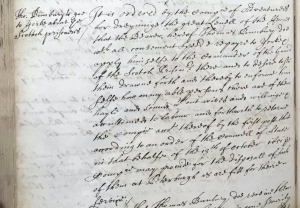

Masters screened prisoners for health before recruiting them as laborers in order to avoid the costs associated with nursing the sick. A fen drainage company in the Bedford Level, north of Cambridge, repeatedly recruited healthy prisoners of war to dredge and build canals for them. In October 1651 the drainage company sent a representative to York to procure Scottish prisoners of war as workers. He was directed to “inform himself how many able persons there are of them hale and sound without wive[s] and willing and accustomed to labour and forthwith to return the Company account thereof by the first post.”4; In May 1652, the company sent another representative to Durham, again specifying that the recruits must be hale, which is to say, free from both injury and disease.5 Healthy men could work the hardest and longest.

In this minutebook, the Company of Adventurers in the Bedford Level directed their agent to procure healthy Scottish prisoners of war to work on their fen drainage project. (Cambridgeshire Archives, R59.31.9.5, fo.117v, detail.)

Recruiters preferred single men most likely because they wanted to avoid the expense of caring for prisoners’ wives’ health, especially during childbirth. Today pregnant prisoners are amongst those considered for early or temporary release from prisons, although the practice of keeping incarcerated women bound during child-birth still prevails.6 There is little evidence about the treatment of captured dependents in the 1650s, and this makes the one mention of women “big with child” in the fens all the more valuable.7 In the source, local villagers petitioned the drainage company to take responsibility for any costs associated with Scottish workers’ babies, thereby reserving locally raised charitable funds for local people. The released prisoners were not welcome by their neighbors in the fens; even their infants did not inspire sympathy.

Prisoners of war faced extra challenges in holding their masters to established standards of care. As displaced “strangers” with degraded social status and few if any friends and family in their new communities, they could not rely on the same safety net as civilians. In insisting that the drainage company provide for their servants, the neighbors in the fens expressed anxiety that, because these foreign servants came from captivity, their new masters would not feel beholden to typical contractual obligations. Early modern English masters generally entered verbal or written contracts with their servants. They were expected to provide servants with the necessities of life, including medical care as needed. The masters of civilian apprentices and domestic servants often fell short on this count, which we know because their subordinates duly took them to court for their failure to provide.

We do have some evidence that the Scottish prisoners sent to Massachusetts in the 1650s were provided with medical care by their masters. The leading minister John Cotton bragged to Oliver Cromwell that “Such as were sick of the scurvy or other diseases have not wanted physick and chyrurgery.”8 This claim seems to have been true: the account book for the ironworks company in Lynn and Saugus, Massachusetts, list payments to five men and one woman for “physick” or nursing and medicine.9 While presumably welcome, this succor came only after forced transatlantic transportation and dispossession. The healthcare provisions for other prisoners-turned-servants remain unknown. Today, released prisoners face similarly grave problems.10

This history raises pressing questions about the conditions that released prisoners will find in the present crisis. How will such prisoners access healthcare, especially in countries without universal healthcare systems? Some released people might be able to make claims to protection, humanitarian aid, and civil rights based on a certain status, for example as citizens or refugees. Will their societies recognize these claims, or re-categorize them in convenient ways that exclude them? Health is a marketable quality, and jobs often come with social benefits. Will we see more resources go to prisoners who can work in lockdowns? These are all questions that the historical study of prisoner releases suggests we would be wise to ask now.

Footnotes

1I would like to thank Marisa Fuentes and Marianne Potvin for their comments on drafts of this post.

2Joseph Neff, “North Carolina Prisoners Still Working in Chicken Plants, Despite Coronavirus Fears,” The Marshall Project, March 19, 2020, updated March 25, 2020, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/03/19/north-carolina-prisoners-still-working-in-chicken-plants-despite-coronavirus-fears.

3For example, Cambridgeshire Archives, hereafter CA, R59/31/9/5, fo. 115r, Oct. 1651.

4CA, R59/31/9/5, fo. 117v, 16 Oct. 1651. I have modernized spelling of all quotations in this post.

5CA, R59/31/9/5, fo. 212v, 3 May 1652.

6Eric Allison and Rowena Mason, “UK Prisoners with Flu Symptoms Forced to Share Cells with Those with Covid-19,” The Guardian, March 31, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/31/uk-prisoners-covid-19-symptoms-forced-share-cells.

7CA, R59/31/9/5, fo. 224v, 29 May 1652.

8John Cotton to Oliver Cromwell, 28 July 1651, in The Correspondence of John Cotton, ed. Sergeant Bush, Jr. (Chapel Hill, 2001), 461, as quoted in Marsha L. Hamilton, Social and Economic Networks in Early Massachusetts: Atlantic Connections (University Park, Pa., 2009), 43.

9Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Mss:301 1650-1685 L989, f. 103–105, 129.

10Christie Thompson, “Freed from Prison After 26 Years—Into a Coronavirus Hotspot” The Marshall Project, April 1, 2020, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/04/01/freed-from-prison-after-26-years-into-a-coronavirus-hotspot.