by Dr. Mark Hailwood (University of Bristol)

Those of us historians intent on exploring the world of ordinary women and men in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries conduct a lot of our research by looking at surviving examples of what such people read–for instance, cheap printed broadside ballads–or of what they wrote–take, say, Joseph Bufton’s notebooks. These materials are fascinating and undoubtedly useful, but regular readers of this blog might understandably find themselves wondering about the validity of this approach, and asking themselves a simple but important question: to what extent could the lower classes of England actually read and write in the seventeenth century?

David Teniers the Younger ‘Peasants Reading a Letter…’ But could they?

It’s a fair question, and has important implications. Matters which I explore in “Rethinking Literacy in Rural England, 1550–1700” Past & Present No. 260 August 2023 (Open Access). Does this material really provide a window into the minds of the most humble people in Tudor and Stuart society, or were reading and writing skills the preserve of the more affluent, or at least the middling, classes of society? After all, in 1691 the puritan writer Richard Baxter had described his lower-class neighbours as ‘the rabble that cannot read’. Was this fair?

Back in the 1970s the social historian David Cressy came up with a cunningly simple way of measuring the literacy skills of our early modern ancestors: counting the percentage of people who could sign their name to witness statements that they gave before the courts. Witnesses in court cases were drawn from across the social scale, and included men and women, so the results could be broken down by class and gender. The methodology was simple: given that it was customary in the period for people to learn to read before learning to write, it was assumed that people who could write out their own signature were fully literate: they would have learned to both read and write. Given, Cressy argued, that there was no particular stigma attached to not being able to sign your own name, it was unlikely anyone would have learned to do this specific task if they were not actually able to write. Those who could not write out their name, who instead usually simply signed documents with a cross, were counted as illiterate.

The results of this approach suggested that in the seventeenth century only roughly 30% of adult men were fully literate, and only 10% of women were. When broken down by social group, the results show considerable divergence across the social scale. Almost 100% of the gentry were literate. The number was around 60% for yeomen (i.e. wealthier farmers) and tradesmen: the groups historians tend to see as the ‘middling sort’ or middle class. But for husbandmen (poorer farmers) and labourers, the percentage that could read and write was only between 15-20%. Put crudely, all gentlemen were fully literate, just over half of middling class men were, but less than 1 in 5 men from the lower classes were. For all classes of women the figure was more like 1 in 10.1

Richard Baxter: ‘the rabble that cannot read’

This might seem to suggest then that reading and writing materials that survive from this period are indeed artifacts of upper and middle class male culture, not the culture of more humble men and women. But there are some problems with these statistics. For a start, as several historians, including Cressy, have pointed out, they are underestimates of reading ability in particular. It was quite common even for the children of the poor to have some schooling, and hence to learn to read, only to be taken out of school at the age at which they were deemed old enough to work on the family farm or in its workshop: around 7 or 8 years old. It was at this age that the teaching of writing skills typically began. It is highly likely then that many people who could not write their name, and would thus be counted as illiterate in these calculations, could in fact read: they were partially literate. Indeed, some historians have suggested that these figures are therefore a massive underestimate of reading ability in the period.2

Moreover, in a recent class I showed some examples of seventeenth-century signatures (not taken from witness statements, but from some petitions by villagers to have alehouses either set up or closed down in their locality) to highlight how this methodology works. In the course of the discussion we identified a number of issues with this process of counting signatures that suggests not only is there a problem here with underestimating reading ability, but that the system of sorting them into ‘signatures’ and ‘crosses’ may well be underestimating writing ability too.

Take, for example, this petition from 1646: sent by the neighbours of one Robert Dowse of Hackleton in Wiltshire to the local magistrates encouraging them to issue him with a license to run an alehouse:

Hackleton Petition

It contains some clear examples of written signatures that suggest their authors were competent at writing, and thus at reading:

The signatures of Thomas Bushell and John Hodges

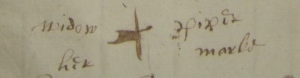

Others clearly fall into the category of simple crosses, where someone with greater penmanship skills has written out the name of the signatory and left a space for them to leave ‘his’ or ‘her marke’, i.e. to sign with a cross:

Widow Piper, ‘her marke’. The blotchy cross may indicate a lack of experience with the quill

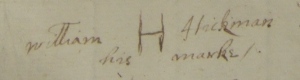

These individuals would be counted as illiterate. Others, however, are not so clear cut. When William Hickman was asked to scratch his mark onto the parchment, he went beyond leaving a simple cross: he sketched out one of his initials:

William Hickman, ‘his marke’

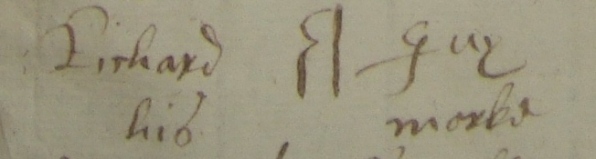

Hickman’s act of one-upmanship might have left an impression on his fellow petitioner Richard Guy. He was invited to add his mark to the list just below the marks of Hickman and Widow Piper. Confronted by their contrasting efforts–the bold H; the blotted cross–Guy may have felt the urge to show that he too was not one of the rabble who could not write: he proffered an initial too, a large R, but it betrayed his inexperienced quill-craft. It was back-to-front:

Richard Guy, ‘his marke’, albeit back-to-front

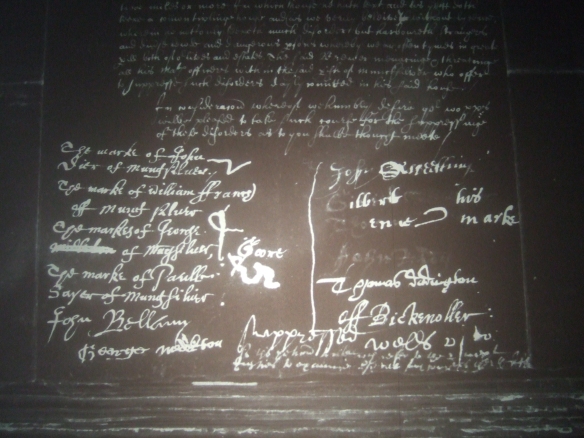

Another example, this time a petition from 1631 by the inhabitants of Monksilver and Bicknoller in Somerset to have a disorderly alehouse suppressed, again indicates a diverse range of literacy skills that are not sufficiently captured by the categories of ‘literate’ and ‘illiterate’:

Signatures on a petition from Somerset

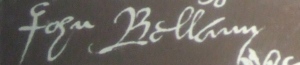

Once more, we have some polished full signatures:

John Bellamy

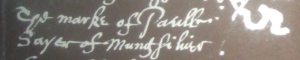

Yet we also have some marks that do not even come up to the standard of a simple cross. Paul Sayer’s blotted squiggle might well be evidence of an individual with very little experience of ever holding a quill (though it might also be the result of an unsteady hand withered by age):

The marke of Paull Sayer of Monksilver: a splodge

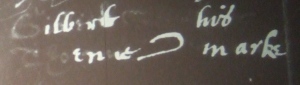

Nor does Gilbert Thorne’s mark seem to suggest much familiarity or confidence with writing. This curt flick also invites us to rethink Widow Piper’s dexterity: by comparison her cross is rather more sophisticated, and may suggest that she was more used to putting pen to paper than Sayer or Thorne:

Gilbert Thorne, his marke

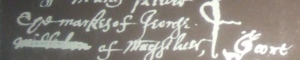

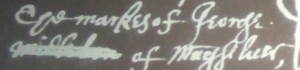

Most intriguing of all though is the signature of the man I will call George ‘Middleton’ (as you will see his surname is very difficult to decipher – I’m open to advances):

George ‘Middleton’ of Monksilver

First of all, you need to ignore the large cross that looks like a big lower case ‘q’. This is in fact the mark of the previous petitioner, who has signed in the wrong place (easy to do, presumably, if you cannot read). Well, I say ignore, but first note that the cross has been made without removing the quill from the parchment, which could indicate a greater degree of skill than a two stroke cross. It’s joined-up handwriting. Even simple crosses, then, can reveal a diversity of calligraphic ability.

When we look past this cross, we can see that George has not left ‘his marke’ in the form of a cross, or even an initial. It seems as though he has attempted to write out his Christian name, albeit misspelled, in full:

‘Geore’

What is more, if we look back to where a more skilled writer has set George’s name down for him to place his mark next to, we see that they have in fact written, uniquely, that what will follow are ‘the markes‘ of George Middleton, not the more routine singular ‘the marke’:

‘The markes of George…’

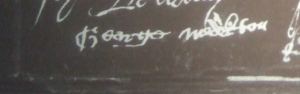

Perhaps George had requested for it to be phrased this way, insisting to his fellow petitioners that there was an important distinction between his writing ability and that of those who could only put a cross beside their name. Why, though, is his surname crossed through? Here is my theory. Imagine his embarrassment when, after confidently insisting he could do ‘markes’ plural, he managed to omit the second ‘g’ from his name. It was a blemish that this proud petitioner could not bear to let alone. So, he decided to up the stakes. He struck out the belittling lines where another man had had to write out his name for him, and down at the bottom of the sheet, below all the other signatures, he endeavoured to sign his own name in full. This time, albeit with a shaking hand that left a spidery ‘George’ and a cramped ‘Middleton’, he succeeded in making his way into the ranks of the ‘literate’:

The fully literate ‘George Middleton’

Perhaps this is being too fanciful. Is it really the same hand as the first misspelled ‘Geore’? The ‘G’ is certainly not identical, but then would we expect an inexperienced writer to consistently produce identical characters? I admit that we can’t be sure, but even if we put this example aside we can see that the range of signatures on these petitions reveal subtle differences in writing ability: even two simple crosses can be compared and contrasted to tell a story about the varying level of skill with which petitioners could handle a quill. This is important because it demonstrates to us that these gradations in ability mattered to ordinary people at the time: many signatories showed great determination to demonstrate that, with their use of an initial, for example, they were not on the bottom rung of the literacy ladder. It suggests that status, and its handmaiden stigma, clung closely to the literacy abilities of even relatively humble people.

I may be pushing this material too far, but I think these signatures are fascinating. Using them to produce broad statistical estimates of reading and writing ability in the period is, undoubtedly, very useful, but reading them closely has the potential to reveal so much more about the spectrum of literacy that existed in this society. Sorting these signatures into the ‘literate’ and ‘illiterate’ results in the lumping together as ‘illiterate’ many people who would in fact have had a wide range of at least some reading and writing skills. An illiterate rabble they were not.

This post originally appeared on The Many-Headed Monster blog under the same title on 13th October 2014. It is reproduced with the agreement and consent of the author. All images in this post were provided by the author. Reference and link to the author’s Open Access article “Rethinking Literacy in Rural England, 1550–1700” in Past & Present No. 260 was added by the Past & Present editorial team.

Footnotes

1David Cressy, ‘Levels of Illiteracy in England, 1530-1730’, The Historical Journal, 20:1 (1977).

2See for example Margaret Spufford, ‘First Steps in Literacy: The Reading and Writing Experiences of the Humblest Seventeenth-century Autobiographers’, Social History, 4 (1979).