by Dr. John M. Collins (Eastern Washington University)

My article, appearing in the May 2020 issue of Past & Present (#247), explores the “law of necessity” in seventeenth century England and is a complementary piece to my book on martial law in the early modern period.1 In this article, I show that narratives of necessity structured many aspects of English law and were vital for state building, both during the Personal Rule of Charles I, the English Civil War, and after. The Long Parliament, for example, invoked it to tax, impress, violate due process rights, break contracts, and to seize and destroy property. Many of these powers, in spite of the wars ending, remained. The modern state was built from emergencies.

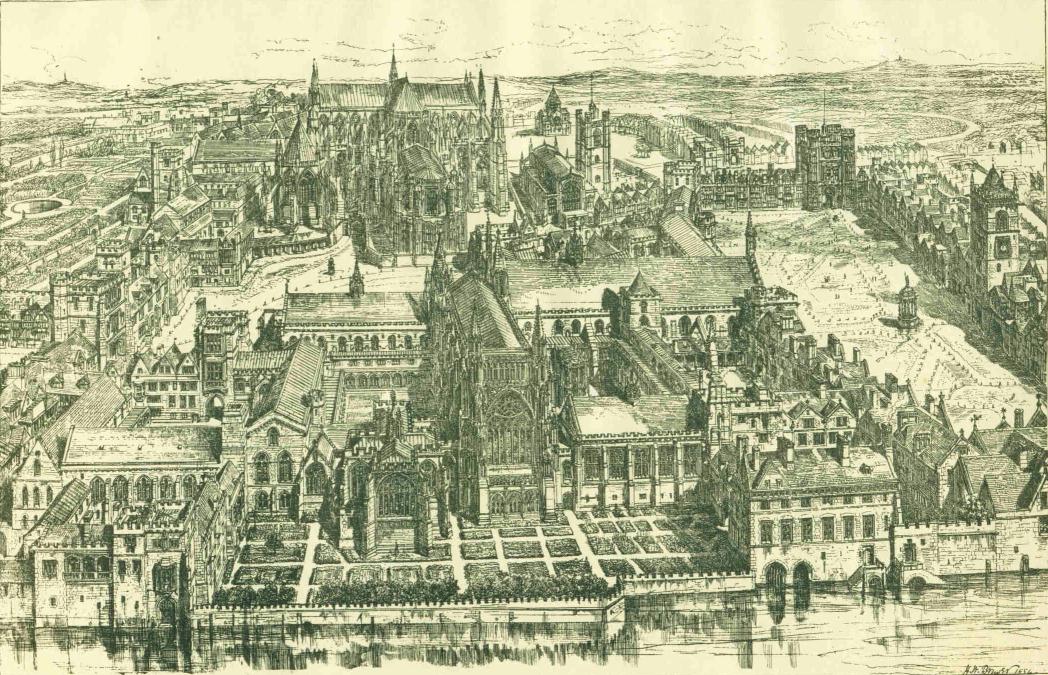

Artist’s impression of the Palace of Westminster in the early modern era, by H.J. Brewer First published: The Builder magazine, 1884 / Republished: parliament.uk / transferred to Commons from en.wikipedia

The article, alas, is more relevant than I (or probably you) would like. Then, like now, the fear of societal calamity, even collapse, allowed the government to take extraordinary powers to save the polity. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the main threats were war and rebellion, with politicians analogizing them to natural disasters like fires. Now, it is the reverse. Politicians have frequently analogized the response to the pandemic to fighting a war.

Like now, claims to necessity in the seventeenth century proved contentious. The problem for narratives of necessity were that they often attempted to justify preemption. Fears of a future flood mandated infrastructural improvements. Fears of a rebellion allowed for the seizure of property or the impressment of men into the navy or army. Many viewed these with skepticism. In an age where readers of politics sought to understand what lay beneath the mask of those in power, claims to necessity appeared as a means to establish absolute power, even tyranny. Opponents of Charles and of the Long Parliament certainly thought so. Distortions of their concerns are currently present in the United States, where I live, as ridiculous protests movements have already begun against social distancing measures.

Traditionally, scholars have thought that claims of necessity existed in a “state of exception” from the legal order. This argument has been most famously associated with Carl Schmitt, the Weimar and then Nazi jurist, who wrote his influential Political Theology in 1922. Quoting Schmitt became something of a cottage industry in the American legal academy after the terrorist attacks in 2001. In this state, the sovereign, or the executive branch in American jurisprudence, could take whatever measures they felt were required to save the polity.

This separation between law and emergency is at best misleading. What this article argues instead is that claims of necessity in fact built upon and adapted the legal regime by generating new law. This is a far easier point to teach now as all of us probably can recognize that a “new normal” shapes our daily lives. What had seemed like a strange fantasy in the beginning has developed into ordinary practices like wearing masks, avoiding physical contact, and conducting business over Zoom or a similar medium. The rest of our legal code has not disappeared. It has simply been altered. It is not difficult, further, to imagine that some of these practices might continue after the pandemic ends. Emergency practices become normal practices.

If I had to rewrite this essay now, I would probably have more sympathy for Alberico Gentili, the late sixteenth century jurist who wrote extensively on the laws of war. For Gentili, fear alone could justify preemptive warfare and emergency measures. At the time, I viewed his claims with cynicism. They were just a means to justify aggressive diplomacy.

Yet fear, while thin on the page, is heavy in life. Fear over mass death, the future of the economy, and of the future of the academy, weighs down on many of us now. It is certainly a much more compelling reason for drastic measures than I would have cared to admit when I initially wrote this article in 2016.

Footnote

1 John M. Collins, Martial Law and English Laws, c. 1500- c. 1700 (Cambridge, 2016).