by Dr. Merle Eisenberg (Princeton University) and Dr. Lee Mordechai (The National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center [USA] and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

“In China, some ten million people died within a span of five years; by the end of 1910, another five million would perish as plague emerged in India, Australia, Scotland, and North Africa, sparking fears that the Black Death…had returned,” or so David K. Randall has recently claimed in his Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague. Randall’s book highlights contemporary Western fears of the world’s impending doom, in this case through the quintessential pandemic – plague. Randall’s book falls within the popular catastrophe genre in academic and mainstream writing, not to mention films and even video and board games. If we follow the message of 1995’s Outbreak, for example, there is the distinct possibility that, without careful quarantine procedures and heroic actions, we are all doomed to succumb to a disease outbreak. In 2011 Contagion took the genre a step further and offered us a “scientifically correct” image of how a pandemic would disrupt all levels of social organization worldwide. As Contagion’s last scenes hint, this collapse will occur inevitably due to human destruction of the climate and the natural environment.

Section from Outbreak (1995), government officials discuss the spread of the fictional virus.

“A Plague Tale: Innocence”, Focus Home Interactive (2019), a video game set during the Black Deat

In our article (Past & Present #244), we explore the first known pandemic to strike the Eurasian world: the Justinianic Plague and the subsequent first plague pandemic (c. 541-750). The well-known story’s outline features in countless introductory courses. The first outbreak of plague devastated the Eastern Roman Empire just as Emperor Justinian (r. 527-565) sought to re-establish Roman hegemony over North Africa, Italy, and Iberia, regions formerly within the Roman Empire. Plague weakened Justinian’s rule at the pivotal moment of his ambitious western re-conquest, resulting in a series of governmental and socio-economic problems, and eventually the loss of further Eastern territories to the early seventh century Persian and Islamic conquests. At the moment it seemed like Justinian might restore the Roman Empire, a tiny bacterium cut his dreams of glory short. By the end of the first pandemic, state and society had transformed, moving away from their ancient Roman roots into something medieval and Byzantine. Antiquity was finally over.

Yet, the more we read the original sources on the plague, the more we became uncomfortable with them. The extraordinary claims made for the effects of this plague lacked the extraordinary evidence they demand. Like Randall’s title, Black Death at the Golden Gate, we realized that the Justinianic Plague story was built upon a series of modern assumptions and conflations of what plague should do, rather than what late antique and early medieval authors told us it did (or did not) do. To bridge this divide, we began situating the key written sources on the first pandemic in their context. Unsurprisingly, once we did this they ceased to be simple nuggets of social and demographic history, but had literary meanings that could be unpacked to reveal a far less certain story. As Kristina Sessa has recently reminded us, environmental and disease history cannot be studied in isolation.

Our article could only touch upon some of the most famous written sources, but we have collected them all, along with the necessary context, in our soon to be launched online app PLAGUE (Plague in Late Antiquity: Gathering the Uncertain Evidence), managed through Princeton’s CCHRI (Climate Change and History Research Initiative). While earlier scholars provided detailed and useful plague catalogues, PLAGUE will offer users the ability to read the primary source in its original language, in translation, and present the necessary context for the source, all of which are beyond the scope of any journal article or book. We encourage others to use the data we offer to reach their own conclusions, to suggest alternative readings within our app, and to teach a new story of late antique plague to future generations. We hope our app will lay the foundation for similar projects on climate, the environment, and disease that challenge existing narratives and try to dig diligently into the details of the past.

A screenshot from PLAGUE, our forthcoming plague app

As we worked on plague we also came to realize the inherent biases in interdisciplinary work that underlay many of the interpretations of the first pandemic, which are also reflected in Randall’s book title, Black Death at the Golden Gate. Plague in modern historical research remains a mashup of different historical plague outbreaks (the Justinianic Plague, the Black Death, and the ongoing Third Pandemic) based on the assumption that because the pathogen that caused them – Yersinia pestis – was the same, the outcome for all periods in history must be as well. As we discuss in our article, although plague tore apart millions of families in India it was never central to governmental planning nor did it transform society. Yet oddly, scholarship has always preferred the Second Pandemic, never the Third Pandemic, as a model for the demographic and social effects of the Justinianic Plague. At the same time, the Third Pandemic supplied its own seemingly arbitrary elements, like black rats and their fleas, as pieces of the plague puzzle to be found in the pre-modern past. In turn, these elements became proof of the presence of the Justinianic Plague with its assumed high death toll.

It is surely significant that the death counts associated with plague outbreaks have not remained constant throughout history, even if scientifically we do not know why. At a basic level, environments, social conditions, and even the plague bacillus itself do not remain the same. Why, therefore, should we expect a plague pandemic to lead inevitably to a massive mortality event that changes the course of history? Plague has become a de facto easy – and seemingly irrefutable – explanation for a hard question: what happened to people who lived through the “fall of Rome?” We are quite certain the population of the empire decreased over the course of late antiquity, but the Justinianic Plague allows us to answer this question all too easily, ignoring the experience of the people who lived through these centuries by postulating that plague killed them all. Rather than assume plague is the answer, we must instead let the people who lived through these two centuries narrate their experiences through their texts, inscriptions and artifacts.

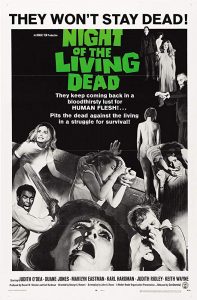

It is also clear that our knowledge of past plagues cannot be separated from current interests in a future global pandemic. Even at a brief glance, trends in studies of the Justinianic Plague (additionally, our forthcoming article in Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies surveys the literature from 2000-2018) mirror trends in films about mass death catastrophes – both real and imagined. These correlations may be linked and require further study. For example, the emergence of contemporary Justinianic Plague studies dates to the late 1960s, the same period in which the zombie film genre was largely created by George Romero in Night of the Living Dead (1968).

Original poster for George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968)

Both received relatively little attention until after 9/11, following the anthrax envelope attacks (2001), as well as the completion of the Human Genome Project (2003) and the further evidence of catastrophic climate change and environmental destruction (e.g. Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth). Over the past two decades, both plague studies and zombie films have witnessed exponential growth. Both developments may stem from the same source – our (Western) contemporary obsessions with past and future catastrophes. Guy Middleton, for example, has recently pointed out the close connection between ancient history and the modern myths we use to understand it, suggesting a theoretical context for such an explanation. The Justinianic Plague may be yet another case study.

Notably, our article could not have been written alone. Writing histories of large-scale disease outbreaks across linguistic and scholarly traditions and over a hundred years of historiography is difficult if not impossible for individual scholars. As a western early medieval historian and a Byzantine historian with different training, we could only have written this article by pooling our combined skills and approaches to collaborate closely and synthesize our knowledge. Given the relative paucity of written sources on the plague, we had to read archaeology, ancient DNA, paleoclimate science, and other methodologies we encountered in CCHRI conferences and workshops to situate each type of evidence in its context using the critical thinking of our own discipline. The PLAGUE project required even more linguistic specialists, who have added their deep knowledge of sources to our own to create a team of researchers who can now work across genre, linguistic, and historical barriers to situate all plague outbreaks in their context. Our experience suggests that future interdisciplinary undertakings such as these would require similar close collaboration.

Plague studies will undoubtedly continue to expand and grow over the coming years as new evidence emerges. We welcome and encourage further debate and challenges to our ideas on this topic moving forward, as we all attempt to understand the Justinianic Plague in further detail.