news and updates on the Past & Present Blog

BLOG

"Charity After Empire British Humanitarianism, Decolonisation and Development" published by Former Past & Present Co-Editor

By Josh Allen - January 30, 2026 (0 comments)

by the Past & Present editorial team

Former Past & Present Co-Editor Prof. Matthew Hilton (Queen Mary, University of London) has a new monograph Charity After Empire British Humanitarianism, Decolonisation and Development published by Cambridge University Press in the Modern British Histories series.

The books blurb explains it explores:

“Why did charity become the outlet for global compassion? Charity After Empire traces the history of humanitarian agencies such as Oxfam, Save the Children and Christian Aid. It shows how they obtained a permanent presence in the alleviation of global poverty, why they were supported by the public and how they were embraced by governments in Britain and across Africa. Through several fascinating life stories and illuminating case studies across the UK and in countries such as Botswana, Zimbabwe and Kenya, Hilton explains how the racial politics of Southern Africa shaped not only the history of international aid but also the meaning of charity and its role in the alleviation of poverty both at home and abroad. In doing so, he makes a powerful case for the importance of charity in the shaping of modern Britain over the extended decades of decolonization in the latter half of the twentieth century.”

The book can be read digitally via Cambridge Core with physical copies avaliable from February 2026. Both can be obtained via the publisher.

Cover image via Cambridge University Press, all rights reserved

Austerity and Food Assistance

By Josh Allen - November 11, 2025 (0 comments)

by Dr. Samantha Iyer (Fordham University)

The United States’s food stamp program is under attack again—again. The current government shutdown has left the nearly 42 million people who rely on the program—now called the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, or SNAP—in a state of uncertainty. Even more fundamentally, in July of this year, Congress passed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which is bound to significantly reduce the number of people who can benefit from the program. That is because the bill increases the state and local costs for administering SNAP, expands the work requirements for receiving assistance, and excludes a range of non-citizens from eligibility. The contraction of government assistance programs is nothing new. It is most often associated with welfare reform under the administration of Bill Clinton in the 1990s. But family food assistance programs have followed a somewhat different trajectory than other government assistance. That trajectory makes the current cutbacks all the more dangerous. For as US policymakers have slashed other welfare programs, these food programs have come to serve as welfare of the last resort.

I examine the distinct path of family food assistance programs in a recent article, ‘Agricultural Workers, Tenant Farmers, and the Midcentury U.S. Welfare State: A View from the Lower Mississippi Valley’ Past & Present No. 267 May 2025. It is often forgotten that the early history of these programs began in the agrarian United States. In both their conception and their execution, they were primarily supposed to serve large commercial farmers rather than the recipients of the aid. The objective of the commodity distribution program created in 1935 was to get rid of food crops that the federal government had bought up to support crop prices—a strategy of disposal that would only later be supplemented by others, such as the foreign food aid program. Agricultural workers and tenant farmers were also among the chief recipients of surplus commodities and, later, food stamps. For them, the programs offered what the National Sharecroppers Union called “ex post facto aid” from the very beginning. Scholars have often argued that agricultural workers and tenant farmers were excluded from the New Deal welfare state. Yet these rural residents did in fact rely heavily on government assistance. It simply took the form of food, under programs that reinforced the racial and class power of white landlords and employers.

What I found from examining petitions, testimonies, oral histories, and government records was that the commodity distribution program absorbed features of the old furnish system of credit in cotton-producing regions of the Mississippi Valley. Under that system, tenant farmers and agricultural workers borrowed food and other commodities from landlords, employers, and merchants at the beginning of the harvest season. They then repaid it at exorbitant interest at the end of the season in the form of a portion of the cotton crop. As mechanized and petrochemical-based faming came to overtake labor-intensive forms of production, the commodity distribution program continued to give landlords and employers power over the subsistence of displaced or underemployed tenants and agricultural workers. That power was now simply mediated by the county governments that administered food assistance programs and in which white planters held much power. Thus, for instance, many counties denied residents food assistance during the seasons in which planters most needed agricultural labor.

Established in 1964, the food stamp program that gradually replaced surplus commodity distribution only reinforced these patterns. It did so through the regular budgeting practices that it demanded. Until 1977, people eligible to receive food stamps had to purchase them, and to do so, they initially had to pay a minimum amount in one lump sum each month. That requirement was at odds with the variable temporal pattern on which tenant farmers and agricultural workers actually earned and spent their cash: It was difficult to save up enough to buy a whole month’s worth of stamps at one time. Counties that transitioned from surplus commodities to food stamps thus saw participation rates rapidly drop. Those who did enroll in the program often had to borrow to buy their food stamps, a need that drove them back into the hands of creditors—often their employers or landlords.

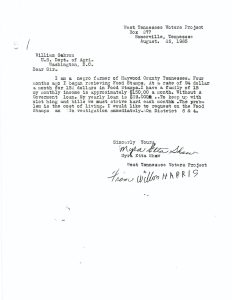

Myra Etta Shaw explains the struggle to buy food stamps for 94 dollars on a monthly income of only 150 dollars. Image Credit: University of Memphis Special Collections, MSS. 41, 2-44.

Activists in the Lower Mississippi Valley demanded a transformation of these programs, and their calls would reverberate to the national level. Beginning in Tennessee in the late 1950s, a succession of rural counties ended their surplus commodity programs in retaliation for efforts by civil rights organizations to register Black voters. In response, local activists set up alternative systems of food distribution and demanded that the federal government step in to distribute surplus commodities. The activists also criticized the punitive nature of the food stamp program and called for a structural transformation. In 1966, tenant farmers and seasonal workers led by Unita Blackwell, Isaac Foster, and Ida Mae Lawrence drove into and occupied an abandoned air force base in Greenville, Mississippi to demand that food and other welfare programs be led by low-income people themselves. The upheaval over food assistance in the region soon drew the attention of national civil rights organization as well as senators like Joseph Clark and Robert Kennedy. This chain of events led to major reforms of federal food assistance programs under Presidents Johnson and Nixon, reducing the cost of buying food stamps and giving households greater flexibility to determine how much and when they bought them. Nonetheless, the punitive character of family food assistance never fully went away. The revised program imposed strict work requirements. And in contrast to cash assistance, food stamps are restrictive by their very nature because no one can live on food stamps alone.

In more recent decades, as cash assistance programs have shrunk in the United States, the food stamp program—renamed SNAP in 2008—has dramatically expanded. As of 2024, an astonishing 12 percent of the US population relies on food stamps. The mid-twentieth-century experience of agricultural workers and tenant farmers has in a sense become generalized as SNAP has come to offer welfare of the last resort for other populations. What the recent revisions to the program threaten to do is puncture the already thin and worn fabric of the social safety net that still remains.

Forthcoming Past & Present Article Awarded the Society for Italian Historical Studies Modern History Article Prize

By Josh Allen - November 6, 2025 (0 comments)

by the Past & Present editoral team

Past and Present was delighted to learn that Dr. Daniel F. Banks has been awarded the Society for Italian Historical Studies’ Modern History Article Prize for his forthcoming Past & Present article “Ships, Guns and Money: The Logistics of Revolution and Garibaldi’s Campaign of 1860”.

In their citation to prize committee consisting of Prof. Giuliana Chamedes (chair), Prof. Michael Ebner and Prof. Steven Soper stated that:

“This article reframes the history of Italian unification and helps us understand a new dimension of why Garibaldi’s campaign against the Bourbon army was successful. Taking us behind the scenes, Banks shows that the Garibaldi expedition was enabled by more than rag-tag idealists and good public relations propaganda; its victories were also made possible through a carefully planned logistical revolution, carried out by businessmen, traders, and economic non-state actors. Shedding new light on the history of capitalism, on Genoa as a geopolitical and revolutionary hub, and on the transnational dimensions of the Risorgimento in exile, we learn how committed radicals mobilized the structures of international capitalism in favor of their cause. Through a rich array of archival, primary, and secondary sources, Banks shows us how complex networks of trade, donations, and shipping criss-crossed the Mediterranean and bolstered the Garibaldi mille. The logistics of revolution thus brought the ships, guns, and money that enabled the “Hero of the Two Worlds” to help create a unified Italy.”

The Society for Italian Historical Studies has conducted a video interview with Dr. Banks:

Our congradulations to Dr. Banks on his scholarship being recognised in way.

To enable all who wish to read “Ships, Guns and Money: The Logistics of Revolution and Garibaldi’s Campaign of 1860” to do so our publisher Oxford University Press had made the article free to read over the coming months.

What Was at Stake in the Maria Luz Incident

By Josh Allen - October 6, 2025 (0 comments)

by Dr. Bill Mihalopoulos

My recent article “Liberty, the Maria Luz Incident and the liminal legal status of Chinese indentured labourers and Japanese licensed prostitutes” in Past & Present No. 268 (August 2025) focused on the celebrated Maria Luz Incident (1872), which involved Chinese labourers on board a Peruvian ship anchored in the Japanese waters of Yokohama. The resulting 1872 Japanese court ruling rendered null-and-void the service contracts that bound those labourers to eight years of service. And the ensuing release of Japanese licensed prostitutes from their ten-year indenture contracts was an unforeseen consequence of that ruling.

The prevailing academic opinion is that the legal ruling of the Maria Luz Incident was the seminal moment when rights talk was introduced to Japan. The Japanese ad hoc tribunal, it is said, freed the Chinese labourers from indentured servitude in Peru and for the first time (temporarily) emancipated Japanese women from sexual servitude by attaching the metaphor of slavery to the domestic issue of licensed prostitution. What has captivated scholarship on the Maria Luz case is what the ruling signified for Japan’s modernization makeover. Was this the watershed moment when modern Japan invested in notions of personal rights, justice, and equity?

Image from “Yokohama kōeki seiyōjin nimotsu unsō no zu/Western traders loading cargo in Yokohama” by Utagawa, Sadahide, 1807-1873, prints published 1861. Images via Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002700230/

“Liberty, the Maria Luz Incident and the liminal legal status of Chinese indentured labourers and Japanese licensed prostitutes” departs from existing scholarship in a subtle but fundamental way. I chose a different route by looking at the “prehistory” of the Maria Luz Incident. Namely, the difficulties mid-nineteenth century free labour ideology faced in differentiating the line between facilitation and coercion when it came to indentured labour migration. The article investigated the contingent processes and complex chain of specific events and conditions that crystallized around the Maria Luz Incident:

- The abolition of slavery in British possessions

- The creation of mixed commissions to adjudicate the legality of slave ship captures

- The normalization of indentured labour as ‘free labour’ in the British social imaginary by reducing the freedom offered to South Asian and Chinese labourers to the choice to enter service as a wage labourer

- A Britain that saw itself as the embodiment of modernity and civilization, which had abolished slavery in its territories and was duty bound to carry that message around the world

- And the actions of British diplomatic and legal representatives in East Asia who saw the events unfolding in the Yokohama foreign settlement as an opportunity to disrupt the Macao trade in Chinese labour because of the arbitrary use of force and physical restraint during transit from Macao to Cuba and Peru.

The Maria Luz ruling was not predicated on any abstract ideas of freedom and human rights. The ad hoc tribunal was convened to clarify who owned the labour of the ship’s human cargo, and to determine whether the captain’s use of force and physical restraint to discipline the indentured workers in transit was justified. Moreover, the judgement of the Japanese court was recognized as legally valid because all foreign and domestic officials involved in facilitating the hearing accepted as uncontested fact that the Japanese legal system was compatible with the principles of British common law. This was eight years prior to the Meiji Criminal Code (1880) and twenty-six years before the Meiji Civil Code (1898) were enacted to render Japan’s legal framework compatible with Western legal systems!

The release of Japanese licensed prostitutes from their contracts in 1872 was an unintended consequence. It was a course of action taken by the Japanese government to make that legal fiction that Japanese law was compatible with British common law into reality. The reforms in Japanese licensed prostitution carried out by the Japanese government in 1873 grafted the notion of consent used in British common law for indentured labour contracts onto the procedures of existing nenki hōkō ((limited time debt bondage) service employment contracts. The result was that the validity of contracts between women and brothel owners began and ended with the signed contract between both parties based on the British common law principle of law as the effect of a transaction. The legal principle that recognized contractual transactions as voluntary acts that produce specific legal outcomes, which the law then recognized and enforced.

Image from “Yokohama kōeki seiyōjin nimotsu unsō no zu/Western traders loading cargo in Yokohama” by Utagawa, Sadahide, 1807-1873, prints published 1861. Images via Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002700230/

The next stage of my research, if my status as independent researcher allows, is to examine the interplay of new forms of legal and religious knowledge introduced to Japan between 1890 and 1905 by Japanese evangelical Christian associations and the emergence of new demands for the abolition of licensed prostitution. These new forms of legal and religious knowledge, it is argued, enabled Christian abolitionist activists to challenge the legality of licensed prostitution by claiming it was a chattel slavery because the contracts between licensed prostitutes and brothel owners robbed the women of their right to free cessation (jiyū haigyō).

The working hypothesis is that the line between facilitation and coercion became especially blurred over the regulation of licensed prostitution in prewar Japan because of the coexistence of two incongruous legal approaches that nevertheless shared the same legal lexicon and common law provenance.

Japanese interpretation of consent in contract followed British common law prescript that limited freedom to the specific and narrow understanding as the choice to enter service. This utilitarian legal approach treated licensed prostitution as a technical matter in terms of the right balance between control and freedom, focusing on benefits over harm. The freedom for females to enter service contracts with brothel owners was deemed a necessary liberty for individual women who had no other recourse in dealing with the precariousness that came with insecure employment and deteriorating social conditions.

Japanese Protestant abolitionists advocated a postbellum United States legal approach that perceived the fundamental function of law and legitimate government as protecting the sovereign and inalienable property rights of individuals. This was a rights-based approach that defined contract freedom as the foundation of all rights and an expansion of choice. This rights-based legal approach challenged contracts drawn on the precedent set by the Maria Luz ruling on the grounds that the contracts violated the natural right of women to quit their employment at will, and thus were nothing less than a form of sexual servitude. Japanese evangelical Christians championed this legal approach because it resonated with and amplified the immense spiritual and social importance they placed on free will, the importance of personal decisions in shaping one’s spiritual life, and the public implications of private choices when it came to liberating Japanese society from the power and bondage of sin.

Lastly, the set of questions pertaining to Japanese prewar licensed prostitution system and what constituted the dividing line between consent and coercion, freedom and slavery, remain live even today. The examples below indicate how they frame and fan the fires of the sexual slavery/military ‘comfort women’ controversy in the twenty-first century.

Example One

On 31 January 2007, Californian Congressman Mike Honda, a third-generation Japanese American, introduced Resolution 121/IH to the US House of Representatives. The bill called on Japan to apologize for forcing women into wartime sexual slavery and to “formally acknowledge, apologize, and accept historical responsibility . . . for its Imperial Armed Force’s coercion of young women into sexual slavery, known to the world as ‘comfort women,’ during its colonial and wartime occupation of Asia and the Pacific Islands . . . .” The House passed an amended bill on 30 July 2007.1

Resolution 121/IH drafted by Honda reformulates the prewar Japanese evangelical rights-based approach to address the sexual slavery/military “comfort women.” While also emphasising the public implications of private choices when it came to liberating Japanese society from the power and bondage of past sin.

Example Two

The response of Japanese politicians to the resolution as it made way through the various House committees was defiant. None more so than the comments made by Nakayama Nariaki, March 1, 2007. A former education minister from September 2004 to October 2005, Nakayama was the leader of a 130-member-strong clique within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party that successfully erased all mention of the comfort women from junior-high school history texts authorized by the Education Ministry. Nakayama asserted that the women who worked the comfort stations were not coerced but were “professional prostitutes” who “voluntarily” entered a service employment contract that established an employer–employee relationship between the women and the “private contractors to provide a basic service.” Nakayama compared the “running of the [military] brothels to college cafeterias run by private companies, who recruit their own staff, procure foodstuffs and set prices.”2 Thus the private contractors, not the Japanese government, bore culpability for alleged abuse at that occurred in the war zone field brothels during the Asian-Pacific War.

In his response to Resolution 121/IH, Nakayama utilises the very specific and narrow understanding of consent and choice adapted by Japanese law since 1873 from British common law prescripts the defined freedom as the liberty to enter service.

Footnotes

1Kinue Tokudome, “The Japanese Apology of the ‘Comfort Women’ Cannot Be Considered Official: Interview with Congressman Michael Honda,” Japan Focus, posted May 31, 2007. http://japanfocus.org/products/topdf/2438

2Mike Honda, “Comfort Women,” Congressional Record Volume 153, Number 38 (Tuesday, March 6, 2007), Extensions of Remarks, Pages E465–E466, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-2007-03-06/html/CREC-2007-03-06-pt1-PgE465-4.htm

Programme and Registration for Fons: Primordial Origins from Myth to Archaeology

By Josh Allen - September 24, 2025 (0 comments)

Received from Dr. George Brocklehurst (School of Advanced Study, University of London)

Dates: 5 – 6 November 2025

Location: Magdalene College, Cambridge CB3 0AG

Programme (as of 22 September 2025)