by Josh Rhodes (Conference Co-organiser)

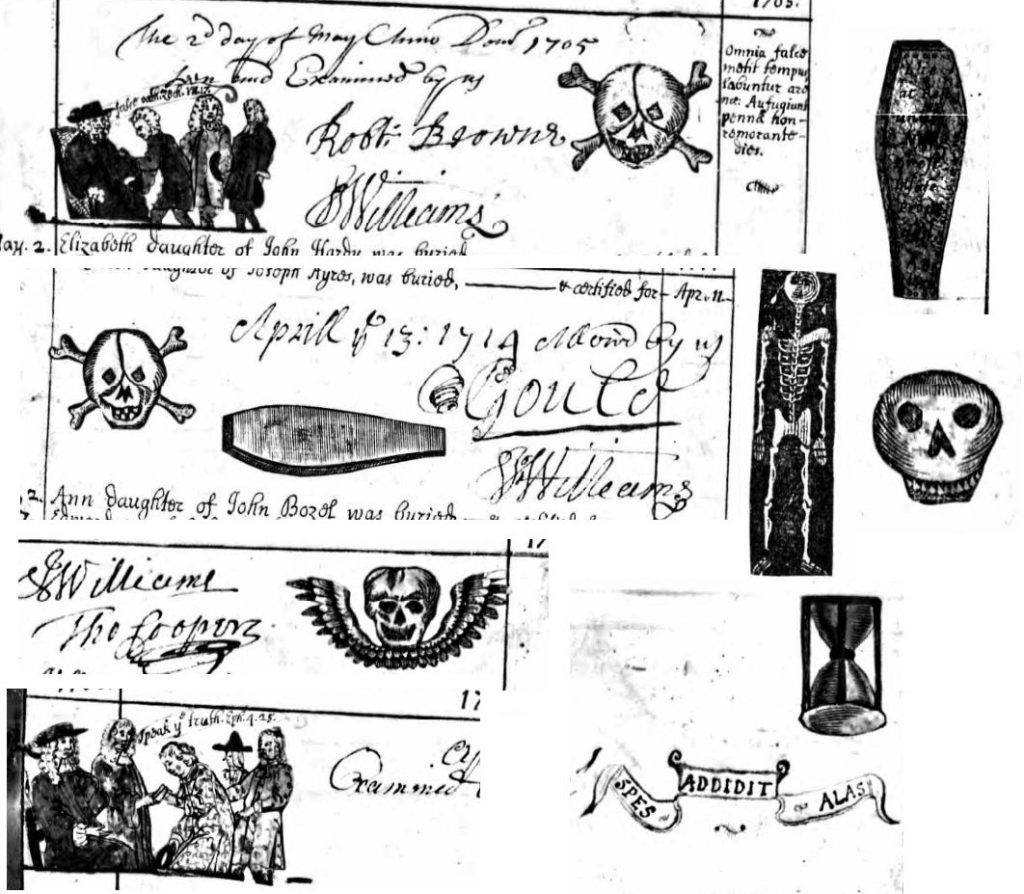

It’s now three weeks ago that the second annual Centre for Early Modern Studies (CEMS) PGR conference at the University of Exeter welcomed scholars from across the UK and beyond to discuss the varied aspects of life and death in the early modern world. I recently found out (having Googled ‘advice for writing a conference report’) that to achieve maximum impact the standard advice is to publish conference reports within 48 hours of the event. But it was a serendipitous find yesterday, as I was searching for a man named Joseph Croad in the burial registers of Puddletown parish in Dorset (scroll down to find out how I got on), that prompted me to write this report. Perhaps you’re thinking, surely burial registers are suitably morbid to be enough of a reminder of all things #EMLifeDeath? Not so. I was so engrossed in looking through the lists of names for any mention of the surname ‘Croad’, that I didn’t notice the striking mortuary doodles on the page until a colleague pointed them out. The doodles contain classic death symbolism: there are scythes, skulls, skeletons, an hourglass, and a coffin. It so happens then that I’d stumbled across several perfect candidates for our conference logo three weeks after the event, and so with total disregard for the ‘48-hour rule’, what better moment to reflect on the proceedings of the conference?

The ‘Living Well and Dying Well in the Early Modern World’ conference gave PGR students the opportunity to exchange ideas and establish networks and contacts with fellow postgraduates and academic staff from universities across the UK. In line with the aims of the interdisciplinary CEMS research group at Exeter, the conference drew together speakers from a range of humanities disciplines, in particular History, English, and Drama. This was reflected in the broad range of sources and methodologies on show. Court records proved popular, as did plays, novels, poems, and ballads. Records of land transactions, household accounts, diaries, and wills also made an appearance. Moving beyond textual sources, some papers considered paintings while one used practical acting workshops to reconsider assumptions about the staging of Shakespeare’s plays.

The interdisciplinary nature of the conference afforded us the luxury of two keynotes: Dr Lucy Munro (King’s College London) and Dr Amy Erickson (University of Cambridge), representing drama and history respectively. As the opening keynote of the conference, Dr Munro kicked us off in style as she traced death’s paper trail in the lives and works of Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. Dr Erickson’s keynote was enjoyed by all and detailed the profitable fan-making business of Esther Sleepe, mother of the author Fanny Burney. Erickson demonstrated her skill and perseverance in reconstructing the working lives of the Sleepe and Burney women (albeit sparked by a chance finding while looking for female apprentices!) in the face of traditional approaches that privilege male economic activity over women’s.

Many of the conference papers directly addressed questions about what it meant to ‘live well’. Some considered spiritual and moral well-being while others focused on the social and economic lives of early modern individuals. And so, we heard about how early modern English astrological diagnosis was linked to conceptualisations of life expectancy. We learned that the language of satirical poetry can be used to recover concepts of patronage and grandeur and help us understand what it meant to live well as a courtier in early modern India. One paper revisited assumptions about the gender wage gap using seventeenth-century household accounts, while another demonstrated the broad socio-economic base of subtenants, a group of people previously considered poor and marginal.

Other papers were more concerned with the question of how ‘living well’ was represented, such as how the lives of eighteenth-century English public figures were used as positive and negative examples of how to lead a good life. Others paid more attention to when things didn’t go so well: one paper considered the mental and physical health of bankrupt tradesmen in eighteenth-century England. Moving from bad to worse, there was also consideration of murder from a range of standpoints. One paper used the last dying words of murder victims to shed light on early modern concepts of friendship and forgiveness. Another uncovered the often-neglected violent acts perpetrated against single pregnant women in eighteenth-century Wales.

Several papers considered the lead up to, and immediate aftermath of, death. Deathbed rituals practised by London Catholics were shown to be key moments at which prescription and practice diverged. Other papers considered aspects of post-death ritual, such as the development of coffin furniture in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century London. Responses to public death in the English Ars moriendi tradition were considered in one paper, while another considered how a woman might attain a ‘good death’.

Naturally, the works of Shakespeare appeared in several papers. We saw a reappraisal of early modern female agency on the stage through the theoretical framework of disability studies. The role played by announcements of death in plays was the focus of one speaker, while another considered practical staging questions and the implications for the safety of boy actors.

This conference was organised by PGRS for PGRS. It was attended by academic staff from several universities, and benefitted immeasurably from the virtual engagement of many postgraduates and academic staff via Twitter. The conference organising committee consisted of three University of Exeter postgraduates: Sarah-Jayne Ainsworth, Harry McCarthy, and myself (Josh Rhodes). Sarah-Jayne is a PhD candidate in the Department of English, whose research looks at women’s voices and identity in women’s writings and wills. Harry is a SWW DTP candidate in the Department of English at the University of Exeter, and the Department of Theatre at the University of Bristol. His research considers the training and performances of boy actors in the dramaturgy of Shakespeare and his contemporaries through a combination of theatre history and practical performance work. I’m an ESRC-funded History PhD candidate and my research re-evaluates the ways historians have defined and measured English capitalist agrarian development, with an emphasis on reconstructing patterns of subtenancy.

And, in case you were wondering, I found Joseph Croad on the pages of the Puddletown burial register for 1715/6. He was buried on 15th January, leaving behind a widow, Agnes, who soon remarried a blacksmith called John Gillet.1 The brilliantly detailed Puddletown census tells us that in 1725 John and Agnes lived in the second house on Chine Hill, about a mile west of Puddletown.2 They lived there with their three children and made a living from John’s blacksmith work and their 20-acre farm. But the spectre of death, depicted so vividly in the mortuary doodles of Puddletown’s burial registers, was never far away. Only three years later, Agnes lost her second husband.3 She continued the family’s business and paid poor rates for their farm for the next 33 years.4 Our final encounter with Agnes is in death, her name appearing in the burial register on 24th August 1762.5

Past & Present is pleased to support this event and others like it. We welcome funding applications from historians of all fields and time periods at any stage in their career. More information can be found here.

Footnotes

1Dorset History Centre (DHC), PE-PUD/RE/4/1, Ad/D/I/1728/23, Probate Inventory of John Gillet (1728)

2DHC, PE-PUD/IN/7/1, Account of the Population of Puddletown (1724-1821)

3DHC, PE-PUD/RE/1/5.

4DHC, PE-PUD/OV/1/2-3.

5DHC, PE-PUD/RE/1/5.